Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is rapidly transforming the healthcare landscape, offering innovations that enhance patient care, optimize clinical workflows, and improve decision-making processes.1 The integration of AI into healthcare practices is not only reshaping clinical environments but presents both challenges2 and opportunities for healthcare education.3 As AI tools become more prevalent, healthcare professionals including Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists (CRNAs) must be equipped with the knowledge and skills necessary to utilize these technologies effectively and ethically.

The primary purpose of this research was to explore the attitudes of student registered nurse anesthetists (SRNAs) and CRNA faculty toward the integration of AI in nurse anesthesia education. As AI technologies become increasingly prevalent in healthcare, understanding these attitudes is crucial for informing curriculum development and educational strategies.4 This study aimed to: 1) identify differences in perceptions between students and faculty, 2) assess levels of familiarity and comfort with AI, and 3) determine the extent to which they believe AI should be incorporated into educational practices. By examining these attitudes and opinions, we aim to contribute valuable insights that can inform CRNA programs, faculty, and institutions about the optimal utilization of AI in nurse anesthesia education.5

Background

CRNAs play a critical role in the healthcare system, responsible for the administration of anesthesia and monitoring patients during surgical procedures. The increasing adoption of AI technologies in healthcare makes it imperative to integrate AI education into CRNA programs. This integration is essential to prepare SRNAs for future practice, where AI will be a vital component of patient care.4 Understanding the challenges and opportunities associated with AI integration can guide the development of curricula that adequately prepare SRNAs for the evolving technological landscape of healthcare.

Of all the technologies that influence education, few have garnered as much attention as AI.5 With natural language processing techniques and large language models (LLM) like ChatGPT, Bard, and others growing in popularity, AI has made a significant stamp on education.5 Many faculty fear that these types of AI will be used by students inappropriately.5,6 Because these technologies are capable of creating large amounts of written content with only a few prompts, the concern is that students will submit this as their own work without proper citation.6,7

Currently, there is a notable gap in the literature regarding the attitudes of SRNAs and CRNA faculty toward AI.6,8–10 While general education and healthcare fields have begun to explore the implications of AI, specific research focusing on the nurse anesthesia discipline is scarce.8,9 This lack of data and available literature represents a significant oversight, given the unique and vast educational and clinical demands of CRNA programs.8 By exploring these attitudes, this study aims to fill a critical gap in the literature, providing insights that could guide the development of policies and practices for integrating AI into CRNA education.10 Understanding these views will not only help in addressing concerns and misconceptions but also in leveraging AI’s potential to enhance the educational experiences of future CRNAs.10 The researchers hypothesized that there are significant differences in perceptions between these groups.

There is currently very little available research addressing attitudes toward the use of LLM AI in education, especially among CRNA faculty and SRNAs.6,11 As AI becomes increasingly prevalent in healthcare, understanding the perspectives of SRNAs and their instructors is of paramount importance in aspects such as knowledge generation and achievement of students’ learning outcomes.12 This research not only explores the differences in attitudes between students and faculty but also seeks to identify potential recommendations for the effective integration of AI into CRNA education.12

AI typically refers to the use of computer-based technology that can do the work historically done exclusively by humans: creativity, reasoning, perception, and analysis.10 These technologies allow computers to augment or even replace human effort.10 While some fear this technology, it is already upon us. How we use it, along with the potential negative and positive outcomes, will come from adaptation of these technologies, not resistance to them.5 In the field of education, AI holds the potential to enhance learning experiences, personalizing instruction and improving educational outcomes.10 AI even has the ability to review literature, complete data analysis and interpretation, write, edit, and format papers, give career guidance, mental health support, critical and constructive feedback, as well as assessments and grading.5,13

The future of anesthesia education is poised to be significantly influenced by the integration of AI.10 As healthcare increasingly adopts advanced technologies, the inclusion of AI in educational curricula becomes essential to prepare students for the evolving landscape.5 AI can revolutionize anesthesia education by providing personalized learning experiences, facilitating high-fidelity simulations, and offering real-time data analysis.10 These capabilities allow for tailored educational interventions that address individual learning needs, enhance clinical decision-making skills, and improve overall educational outcomes.13 For instance, AI-driven simulations can mimic complex clinical scenarios, providing students with opportunities to practice and refine their skills in a controlled environment, thereby enhancing their readiness for real-world situations.5

The successful integration of AI into nurse anesthesia education hinges significantly on the attitudes of both students and faculty.5 How these technologies are perceived can greatly impact their adoption and appropriate use.10,13 Positive attitudes towards AI can foster a more open and innovative educational environment, encouraging experimentation with new teaching methodologies, learning tools, and the application of available evidence in the use of AI in education applicable to nurse anesthesia education.10,13 Conversely, skepticism or resistance to AI could hinder its implementation, limiting the potential benefits that these technologies can offer.5,8 Understanding the perspectives of SRNAs and CRNA faculty is, therefore, crucial in developing strategies that promote the effective and ethical use of AI in nurse anesthesia education.8

Tool Development

Because no current tool was found to measure SRNAs and CRNA faculty attitudes toward AI, a tool was developed by the researchers of this study. The original 49 item survey solicited information specific to five areas of educational interest: 1) diversity, equity, and inclusion, 2) simulation, 3) ultrasound, 4) social media, and 5) AI. The 49 items were generated, assessed, and evaluated by the Principal Investigator (PI), using a pilot study which consisted of 87 SRNAs and five faculty members. The five experts who reviewed the instrument were experienced faculty members, each with over 10 years of teaching experience in nurse anesthesia education, including several with extensive working knowledge and practical application of AI in academic and clinical settings. This manuscript will present data from the AI portion of the survey.

Attitude Toward Artificial Intelligence Scale Development

In the initial step of the Attitude Toward Artificial Intelligence (AAI) scale development, the PI developed a pool of items focusing on SRNA and CRNA faculty attitudes toward AI. Item review was undertaken by five experts in graduate CRNA programs. Item agreement was based on 100% consensus, resulting in the generation of six items.

The six-item tool uses a traditional five-point Likert-type scale for measuring levels of agreement-disagreement (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Since AI is still new, this scale included a neutral option to allow respondents to express uncertainty when they lacked strong agreement or disagreement. The possible scores ranged from 6 to 30, with higher scores indicating a more positive attitude toward AI. All items are presented in Table 1.

Psychometrics

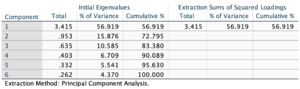

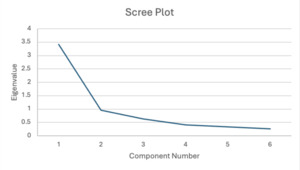

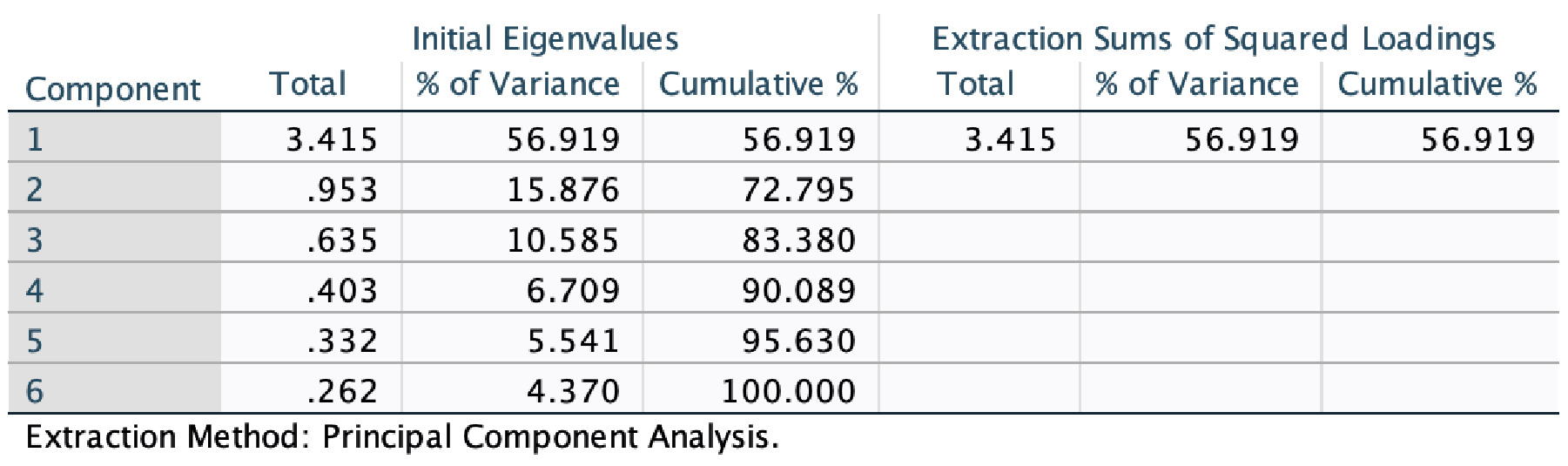

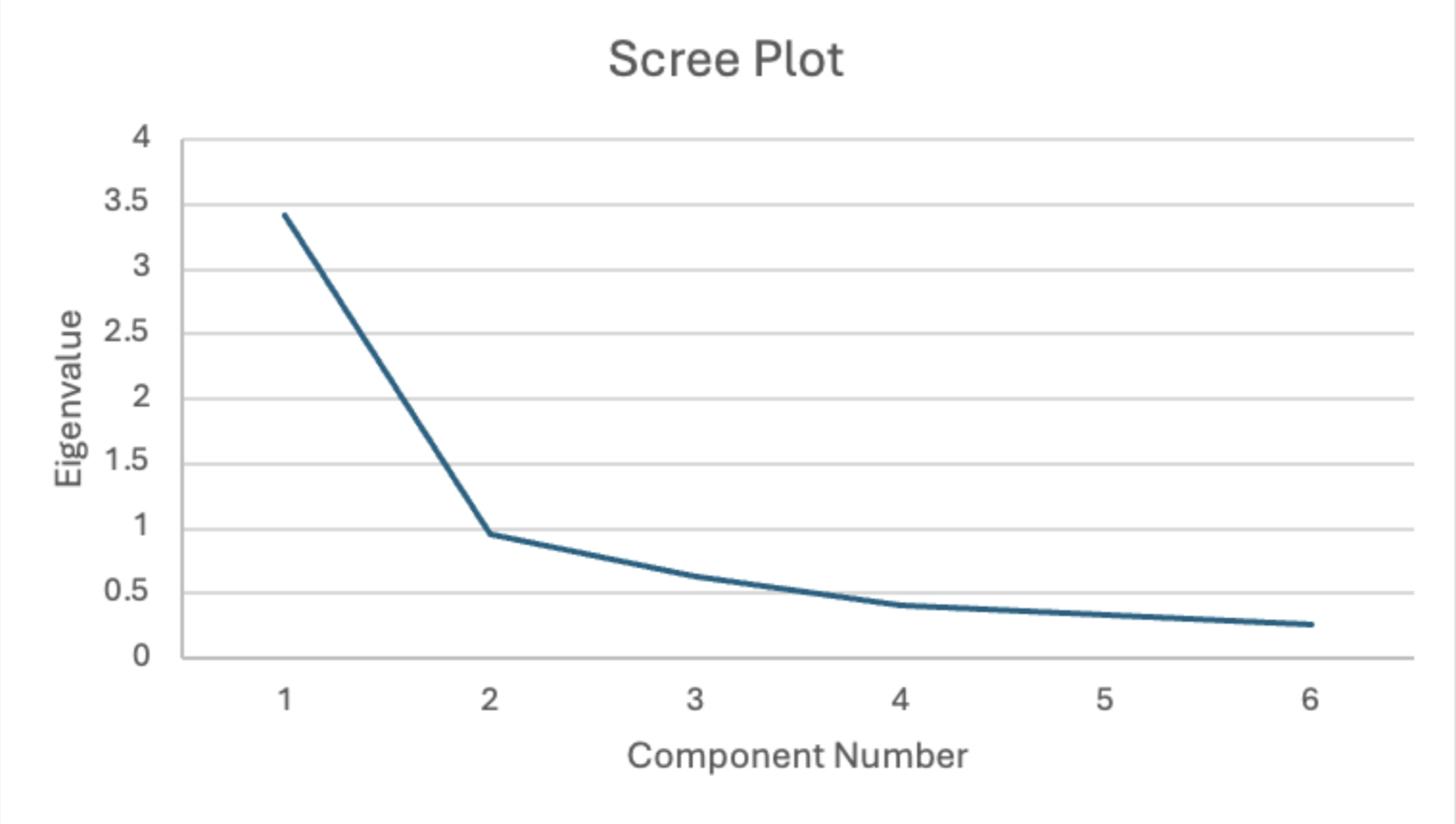

Validity criteria included Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) using the Principle Component Analysis (PCA) extraction method with Varimax orthogonal factor rotation with retention of all eigenvalue > 1.0.14,15 Factors were examined using the scree test, communalities, total variance explained, and component matrix factors. Internal consistency (reliability) was calculated via item-to-total correlations and Cronbach’s alpha.

PCA was undertaken to determine underlying constructs or factors of the six-item tool (n = 404). Kalser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of Sphericity were generated to determine if factor analysis was appropriate.14,15 Results indicated factor analysis was appropriate to undertake: KMO was 0.830, which exceeded the recommended minimum value of 0.6, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (<0.001), indicating that the correlation matrix was suitable for conducting the factor analysis.15 Anti-image matrixes correlations were > 0.5 suggesting all items be retained.16

Six items loaded on a single factor. Five of the six communalities (the proportion of each variable’s variance explained by the factor), after extraction, were above the minimum recommended 0.30 level; item #5 was 0.293, which can be described as marginally (<0.3 and >0.25) defensible.15 The scree plot graph identified one factor to be extracted (see Figure 1). The component matrix indicates large factor loadings > 0.4 on each item.14 Table 1 presents the eigenvalues and total variance explained. After extraction and rotation, there was one component with the data set for the eigenvalue >1. The single factor accounts for a combined 56.9% of the total variance shared by six variables. As a single factor, a rotated component matrix solution was not permitted. Table 2 exhibits diagonal anti-image correlations, communality after extraction, factor loadings data and is a summary of the survey tool.

The decision to retain item #5 was made based on strong factor loading and high anti-image correlations, despite a marginal communality of 0.293. Removing item #5 would have reduced the number of items in the single factor to five. Ideally, at least four to six items per factor are needed for better reliability and accuracy in identifying underlying factors or dimensions.17 The single factor was termed ‘attitude toward AI’. Internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) of the single factor was considered desirable at 0.84.18 The item-to-total correlation ranged from 0.40 to 0.76, indicating strong discrimination between an individual score (item) and the total score.18 All analyses were generated using SPSS (version 29.0.0.0).19

Methods

The purpose of this cross-sectional survey was to explore and compare the attitudes of SRNAs and faculty towards the integration of AI in nurse anesthesia education. The study utilized a descriptive comparative research design, employing an online survey to gather quantitative data on participants’ attitudes.

Recruitment and Study Participants

After the PI submitted the study to the Institutional Review Board at the affiliated university and was granted exempt status, convenience sampling was undertaken at six participating universities that offer nurse anesthesia education. Universities participating in the study were spread out across the United States, with 3 in the Midwest, 1 in the South, and 2 in the Southeast. Students from each participating university were solicited by the study’s site coordinator. Each site coordinator disseminated the survey and consent through its official university platform. The survey was distributed to 459 graduate students from the six participating universities. Total student participation ranged between 45 to 159 as presented in Table 3.

The six-site data collection occurred between March 2023 and January 2024. Students were invited to participate in the voluntary survey during in-person sessions, including university conferences and classes. The invitation was also sent via email. The response rate was high; over 85% of invited students participated in the survey. The survey was distributed to each student only once through their official university platform, and participation was voluntary and anonymous. While it is theoretically possible for the same student to access the survey multiple times, this scenario is unlikely, given the structured distribution process. Additionally, no evidence suggested duplicate responses, and response patterns and demographic data were consistent across participants.

CRNA faculty were invited to participate in the study via email and their respective online platforms. Fifty-eight faculty participated in the study. Faculty data were collected between April 9, 2024, and April 29, 2024. The electronic service SurveyMonkey™ was used for data collection.

Data Analysis

Analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (version 29.0.0).19 Descriptive statistics were generated to describe the population. Frequencies, percentages, estimates of central tendency, and dispersion (e.g., standard deviation) were calculated to describe participants’ demographic characteristics and AI characteristics. The age of respondents was measured using categorical data, while AI was assessed using interval-level data. ANOVA was generated to determine mean differences between site groups. An independent t-test determined differences between student and faculty AI attitudes and scores towards AI. As indicated earlier, factor analysis, EFA with Varimax rotation was undertaken. Cronbach’s alpha was generated to determine the internal consistency of the AI tool.

Survey data were downloaded from SurveyMonkey as an SPSS file. Missing data were removed if five or more items from the AI scale were missing. Fifty-three, or 11.6%, of the original 455 student cases were removed due to missing data. This resulted in 404 valid cases for analysis. There was one missing faculty case, which resulted in a sample size of 58.

Results

Demographics

This survey solicited information from 455 students. A post-hoc analysis was conducted using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.6) to determine the appropriate sample size.20,21 The sample size was enough to attain a statistical power of 0.80.17 Overall, the majority of student participants were White or Caucasian (n = 184, 42.6%) and Hispanic/Latino (n = 141, 33.2%), female (n = 306, 67.3%), and the majority were between the ages of 20-29 (n = 217, 54%). The student participants’ demographic characteristics are presented in Table 3.

Fifty-eight faculty participated in the study. Overall, faculty were White or Caucasian (n = 48, 81.4%), female (n = 41, 69.5%), and equality between the ages of 40-49 (n = 20, 33.9%) and 40-49 (n = 20, 33.9%) as presented in Table 4.

AAI Scale

Student individual score means ranged from 2.80 to 3.13. Group means ranged between 2.64 to 2.87. The overall student mean of 2.80 (SD 0.806) suggests positive AI attitudes. The faculty means ranged from 2.75 and 3.74, with an overall mean of 3.43. Student Cronbach’s alpha was 0.84; while faculty alpha was 0.836. The overall alpha of both populations was 0.84. All alphas indicated a large effect size.17

Student mean difference between the six sites was examined. The ANOVA was insignificant at the 0.05 level, F(5, 397), p = 0.440. An independent t-test was generated to compare student mean with faculty means, which was found to be significant (df =466, t = -5.34) p = < 0.0001. See Table 5 for group item analyses.

Results in Figure 2 are based on collapsing the five-point Likert scale into three-points: those that disagree, those that agree, and those that neither agree nor disagree. These bar charts were created using AI-generated tools from OpenAI’s ChatGPT.

Discussion

This study offers key insights into SRNA and CRNA faculty attitudes toward AI in education.

Interpretation of Results

Item 1. “I have used AI in the past.”

The results show that a significantly higher percentage of faculty members reported using AI in the past compared to students. This disparity likely reflects faculty’s broader exposure to professional and academic environments where AI tools are more commonly utilized. Faculty members may have had more opportunities to engage with AI through research, clinical applications, instructor workshops, or administrative tasks, whereas students may not have encountered AI as frequently in their educational journey. This question likely sets the context for the following items, as SRNAs’ limited experience with AI compared to CRNA faculty may influence their responses throughout the survey.

Item 2. “I have used AI as an aid to complete my coursework.”

The responses to this item also show a significant difference. This suggests that faculty members might integrate AI into their workflows for grading, research, or teaching preparation. In contrast, students’ lower usage rates could indicate either a lack of access to AI tools or a lack of awareness of how these tools can aid their studies. The hesitancy among students might also be attributed to concerns about academic integrity or uncertainty about how to properly utilize AI without compromising their learning experience.

Item 3. “I have positive feelings about AI.”

Both groups generally expressed openness towards AI. For students, the mean of 2.80 (SD 0.806) indicates a slightly negative attitude that approaches neutral (3.0). The faculty group means ranged from 2.75 and 3.74, with an overall mean of 3.43 which trends toward a positive attitude (3.0). This difference could be influenced by the faculty’s greater exposure to the practical benefits of AI, such as improving efficiency and enhancing research capabilities. Students’ more varied responses might reflect a lack of experience or mixed feelings about the potential impact of AI on their future careers and the quality of patient care.

Item 4. “I feel that AI is useful if integrated into my courses.”

Faculty members again displayed a higher mean score compared to students, indicating that faculty are more convinced of the benefits of integrating AI into the curriculum. This result underscores the potential gap between the theoretical understanding of AI’s benefits and the practical application in educational settings. Faculty may recognize the value of AI in providing personalized feedback, automating administrative tasks, and enhancing simulation-based learning, while students might be less aware of these applications or concerned about the complexity and accessibility of such tools.

Item 5. “I feel the use of AI should be limited among students.”

Interestingly, the responses to this item were more aligned, with both students and faculty expressing similar levels of agreement. This suggests a shared concern about the overuse or misuse of AI by students, possibly stemming from worries about academic dishonesty or the potential for AI to undermine the development of critical thinking and practical skills. Both groups seem to agree that while AI has its place in education, its use should be carefully monitored and guided.

Item 6. “Instructors should be teaching students how to integrate AI into their coursework.”

This item showed the largest discrepancy between student and faculty responses. Faculty members strongly agree that there is a need for education on how to integrate AI into coursework, reflecting a recognition of AI’s growing importance in healthcare and education. In contrast, the more moderate agreement from students suggests either a lack of awareness of AI’s potential benefits or uncertainty about how such integration would be implemented. This highlights an educational gap that could be addressed by developing targeted AI literacy programs within CRNA curricula, ensuring that students are equipped with the necessary skills and knowledge to leverage AI effectively in their studies and future professional practice. These findings highlight the need for CRNA programs to incorporate AI literacy.

Discussion: Implications for CRNA Education

The results of this study seem to indicate that while faculty may be eager to incorporate AI in CRNA education, students appear to be neutral. Despite the neutrality of students, it may still be in the best interest of faculty to guide students on how to properly use AI; both the utility and ethics. If faculty are not the ones to show the proper use of AI, students may learn inappropriate or even unethical uses for it. Future studies may explore more deeply the root of students’ uncertainty towards AI.

If CRNA faculty plan to implement AI training, it should address students’ reservations, enhance technical skills, and cover ethical considerations. This can be achieved by offering AI evidence-based workshops to showcase real-world applications, providing hands-on training with relevant AI tools, and facilitating discussions on the ethical implications of AI in healthcare, such as patient privacy and bias. Students should also be given guardrails on how to responsibly use these tools in their education without compromising their integrity. AI can be used in a way that does not lead to cheating or plagiarism. Training should also include developing technical skills through coding and data analysis exercises and promoting interdisciplinary collaboration to understand different perspectives. Finally, fostering a culture of continuous learning through advanced courses and certifications will ensure students remain proficient and adaptable to the evolving AI landscape.

Surprising Findings and Potential Explanations

It was surprising to learn that CRNA faculty are significantly more likely to use AI to complete their work than students. Among faculty, 44% said they have used AI to complete their work compared to only 12% of students. This could reflect the limitations placed on students by faculty to use AI, a lack of familiarity with AI, a fear about self-reporting their use of AI, or a lack of knowledge on appropriate AI citation. It follows that more faculty would have positive feelings towards AI (75%) than students (32%), but we were surprised at the significance of the gap between the two. It makes sense that there is a parallel between positive feelings towards AI and its use.

Lastly, we were surprised that a small percentage of students (32%) wanted their instructors to teach students how to incorporate AI into their coursework. Comparatively, 63% of faculty agreed with that statement. While young people are anecdotally considered early adopters on new technology, it appears that in this space, the older are more receptive than the younger.

Limitations of the Study

This study provides valuable insights into SRNAs and CRNA faculty attitudes toward AI in anesthesia education. However, some limitations should be noted:

-

Incomplete Responses: Eleven percent of responses were excluded due to incomplete survey sections on AI. This exclusion may have introduced bias, as the views of non-respondents could differ from those who completed the survey, potentially skewing the results and limiting generalizability.

-

Sampling Method: The use of convenience sampling at six universities limits the generalizability of the findings. The absence of random sampling and the geographic limitation mean the results may not represent all students and CRNA faculty across the U.S. Findings are not generalized beyond the study population.

-

Limited Scope of AI Applications: The survey focused on general attitudes towards AI in coursework without exploring specific AI applications in clinical settings or advanced educational tools. This narrow focus may have missed important perspectives on AI.

-

Cross-Sectional Design: The study’s cross-sectional nature captures attitudes at a single point in time, making it difficult to track how perceptions of AI may change over time with increased integration into education and practice. Longitudinal studies are needed to observe these changes.

-

AAI scale: The tool requires further psychometric analysis as this is a new tool and hasn’t been used elsewhere.

-

Although the survey was anonymous, it is possible that students hesitated to provide positive responses about AI due to concerns about being perceived as overly reliant on technology or lacking effort, even if such concerns were unwarranted.

-

The data analysis of this study was completed by the authors which could lead to bias. This bias was mitigated by reviewing for internal consistency, but further research could reduce the risk of bias.

-

It is possible that one student could submit more than one result. Although our survey platform used safeguards to mitigate this possibility, the risk was not eliminated.

Despite these limitations, the study offers useful insights into current perceptions of AI in CRNA education and suggests areas for future research and educational development. Addressing these limitations in future studies will improve our understanding of integrating AI into healthcare education and practice.

Conclusion

This study explored the attitudes of CRNA faculty and SRNAs toward the use of AI in anesthesia education. The findings reveal that CRNA faculty demonstrate a higher level of familiarity and comfort with integrating AI into the curriculum compared to students. Significant differences in responses were observed across various survey items, particularly in the perceived usefulness of AI in coursework and the belief that instructors should teach students how to integrate AI into their studies. This gap shows the need for more AI education in CRNA programs. This study provides a foundational understanding of the current perceptions of AI within CRNA education and highlights critical areas for further research and educational innovation.

As AI continues to evolve and become increasingly integrated into healthcare, it is imperative that educational institutions equip both students and faculty with the necessary skills and knowledge to navigate this technological landscape. Future research should aim to address the identified gaps, such as the need for longitudinal studies to track changes in attitudes, perceived attitudes versus actual practice, and the inclusion of more diverse and representative samples and real-time AI studies. By doing so, we can ensure that CRNA programs remain at the forefront of educational and technological advancements, preparing graduates to excel in a rapidly changing healthcare environment. This study emphasized the importance of continually assessing and meeting the educational needs of both faculty and students to enhance effective learning.