Introduction

Background/Significance

Non-technical skills (NTS) are a vital part of any workplace. NTS can be defined as interpersonal skills encompassing communication, teamwork, and leadership, as well as cognitive skills including situational awareness and decision-making.1 These skills contrast with procedural knowledge, technical skills, medical expertise, available medications, equipment, and resources. An estimated 80% of adverse events that occur in the realm of delivering anesthesia can be attributed to a lack of proper NTS.1 Based on this information, proper NTS can prevent medical errors and maintain patient safety in the healthcare system.

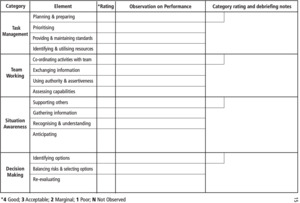

The University of Aberdeen and the Scottish Clinical Simulation Centre collaborated to create the Anaesthetists’ Non-Technical Skills (ANTS), a framework and assessment tool for observing and rating anesthetists’ NTS.1 The abilities measured by this tool include task management, teamwork, situational awareness, and decision making. This tool has proven to be a valid resource for the assessment and development of NTS.2

Many medical errors are due to underdeveloped NTS, yet historically, they have received little attention during institutional learning.1–3 Simulation labs provide a safe and open learning environment for student registered nurse anesthetists (SRNAs) to develop technical and NTS.4 The lack of a validated tool for assessing NTS and behaviors of anesthesia practitioners was a motivating factor behind the creation of the ANTS tool.5 Recent literature supports the ANTS tool’s validity and reliability in various settings, further emphasizing its importance in training and assessment.5 Using the ANTS tool with simulation scenarios may allow for assessment of growth in NTS throughout the nurse anesthesia curriculum.6 This study builds upon prior research related to combined debriefing methods for SRNAs in simulation scenarios and aims to address the gap in understanding how clinical experience correlates with the development of NTS over time.7

Problem Statement/Objective

There is a knowledge gap in current literature regarding clinical experience in SRNA training and its correlation with NTS as measured by the ANTS tool. In this study, researchers examined the concept of clinical experience, as measured in clinical hours, and its relation to developing NTS. The objective was to determine whether a greater number of clinical hours in the SRNA correlates with NTS scores observed in a simulation scenario.

Review of Literature

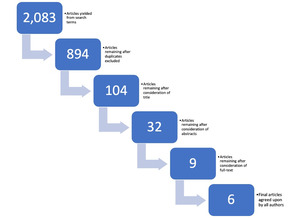

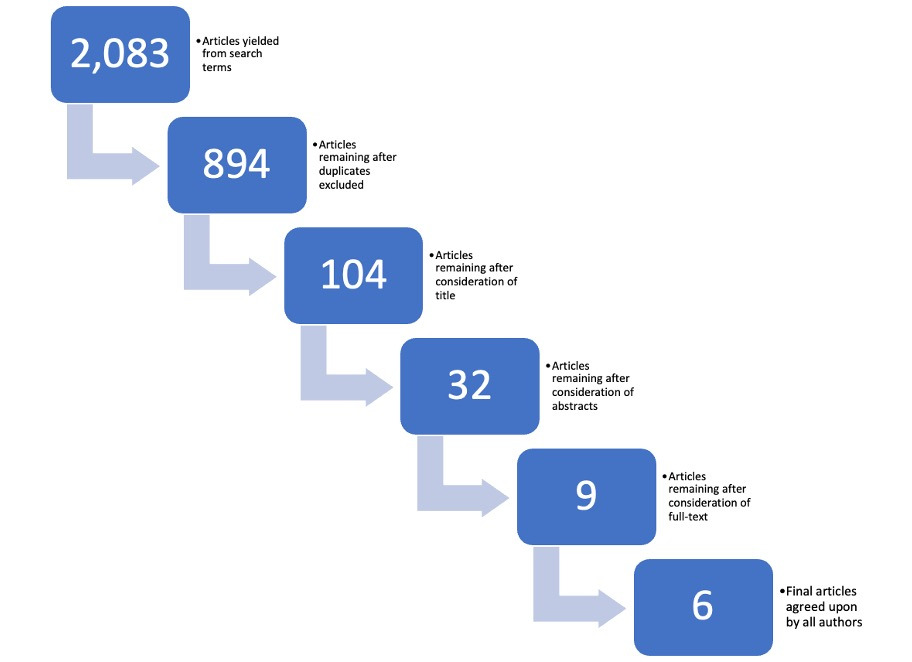

A rapid review of the literature was conducted through a systematic search of 3 databases– PubMed, Embase, and CINAHL. The databases were accessed through the academic institution’s library of health sciences. All databases were explored with the search term “non-technical skills” while using the Boolean operator “AND” in combination with: “anesthesia”, “anesthesia simulation”, “ANTS tool”, “anesthesia clinical experience”, and “student registered nurse anesthetist”. These searches yielded a total of 2,083 articles.

All search results were uploaded to Rayyan. Rayyan is an artificial intelligence tool for systematic literature review that allows blind collaboration between multiple authors for efficiency and objectivity.8 To narrow 2,083 studies down to the final six, 1,189 duplicate studies were excluded. Next, each author conducted a 3-step process. The first pass considered the titles of the studies only, with each author excluding articles inconsistent with the aim of this rapid review. The second pass considered the abstracts of the remaining studies, and the third pass considered full-text articles. Nine full-text articles were chosen by the researchers, with unanimous agreement upon the final 6 articles (Figure 1). Inclusion criteria included articles published within the last fifteen years with relevant themes consistent with the author’s investigation.

There were 6 entries included for analysis: 2 experimental studies and 4 systematic reviews. Included in the articles were works from Canada, Germany, India, Mexico, Norway, and the United Kingdom. Relevant background information regarding the importance of NTS and the question of how to judge them was published by Radhakrishnan et al.4 Amongst all the evidence and discussions, 3 themes emerged:

-

Non-technical skills (NTS) are imperative to the delivery of safe anesthetic care.

-

NTS are difficult to evaluate but should be taught and evaluated.

-

The ANTS tool is valid and reliable in assessing NTS in the anesthesia learner.

The central theme from the literature was the importance of NTS to patient safety during anesthesia delivery. Approximately 70-80% of medical errors are attributed to human error, which highlights its relevance.4,6,9 Flin and Patey4 state that the risk of error is increased when there are insufficient NTS, and this in turn increases the likelihood of an adverse event. Boet et al2 similarly describe NTS as essential to practicing anesthesia proficiently.2 Moreover, there was a strong correlation between NTS and safety in anesthesia practice.10 There is agreement and support amongst the literature that NTS are a vital part of safe anesthetic care.2,4,6,9,10

The next theme appearing in the literature was that NTS assessment is difficult but necessary. Moll-Khosrawi et al6 noticed the absence of any evaluation or assessment tool for NTS; their study aimed to create and validate a tool to do just that. Flynn et al10 set out specifically to develop an NTS assessment tool for use in undergraduate training in emergency medicine and anesthesiology. Boet et al2 also addressed the importance of evaluating NTS. Their study included a measuring tool allowing for assessment and ranking of NTS, thereby allowing anesthetists to reflect and improve upon their personal NTS and overall anesthesia practice.2

The final theme from the literature demonstrated that the ANTS tool is valid and reliable assessing NTS. Each of the 6 articles referred to ANTS as the most used and studied tool. Flin and Patey stated that the “levels of rater accuracy were acceptable and inter-reliability approached an acceptable level”.5 Similarly, Boet et al demonstrated that ANTS “appears to have acceptable validity and reliability for assessing NTS of anesthetists in both simulated and clinical settings”.2 Finally, Sánchez-Vásquez et al9 bolstered the finding and emphasized the ANTS contributed to patient safety.

The discussion around the importance of NTS is robust and ANTS is decidedly the most utilized tool. The existing research does not address whether NTS develops organically over time in SRNAs. The researcher’s intent was to examine if there is a relationship between amounting clinical experience and improved NTS.

Methodology

Study Design

This cross-sectional, observational study compared NTS during a high-acuity, low-frequency simulation between SRNAs with 6 months (Class of 2025) and SRNAs with 18 months (Class of 2023) of clinical anesthesia training. The Class of 2025 is considered the relative control group due to their fewer anesthesia clinical hours as compared to the Class of 2023. The main objective was to investigate the relationship of clinical experience on simulation performance, in the form of ANTS scores. Permission was granted for use of the ANTS tool by its author.

The institutional IRB determined the study to be exempt from consent because the study involved observation of public behavior as stated by the 2018 Common Rule.11 Prior to the simulation scenario, both cohorts were sent an informational email describing the purpose of this study, background information on NTS, and the plan to retrospectively observe simulation visual and audio recordings. The communication informed participants that evaluation would focus on NTS and not clinical outcome of the scenario.

To be eligible for the study, individuals had to be a currently enrolled SRNA at the time of the simulation, over the age of 18 years, and belong to either the Class of 2023 or the Class of 2025. Graduate students from any other class within the nurse anesthesia program were excluded due to timing considerations.

The researchers, SRNAs in the Class of 2025 cohort, individually viewed the recordings and rated non-technical skills using the ANTS tool. Data collection occurred at the Patient Safety and Clinical Competency Center (PSCCC), ensuring a secure location with limited access to maintain confidentiality. Prior to the simulation, the researchers were trained to conduct evaluations using the ANTS tool on simulation training videos that were delivered onsite. The researchers discussed the characteristics of each score on the ANTS tool during the training. The aim was to establish inter-rater reliability, which was in accordance with the tool’s guidelines on validity of use. To maintain the integrity of the study, immediate feedback was not provided on participants’ results. All audio and visual recordings were destroyed after data collection and analysis, per the policy of the PSCCC.

Setting

The simulation scenarios occurred in the PSCCC at the academic institution. The PSCCC provides a conducive environment for individuals or teams from various backgrounds to practice their skills in a high-fidelity, low risk setting. The PSCCC is equipped with audio-visual recording technology, lifelike patient simulators, standardized patients, and debriefing rooms.12

Simulation scenarios are a mandatory component of the nurse anesthesia program’s curriculum for SRNAs. This high-acuity, low-frequency simulation scenario was part of the curriculum that the students participated in regardless of their participation in this observational study. The simulation scenario included 3 standardized patients who played the roles of surgeon, nurse, and surgical technologist. The patient simulator was a Laerdal SimMan 3G controlled by faculty behind a semi-transparent mirror. During the scenario the patient displayed data consistent with the diagnosis of malignant hyperthermia. The role of the SRNA was to identify and manage this rare but life-threatening anesthetic emergency.

Participants

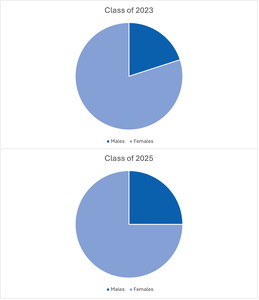

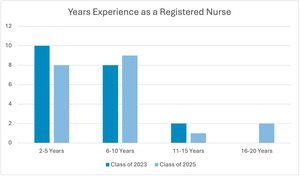

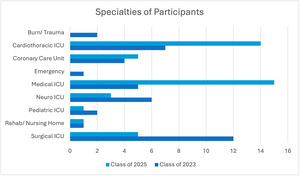

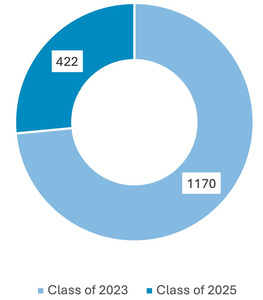

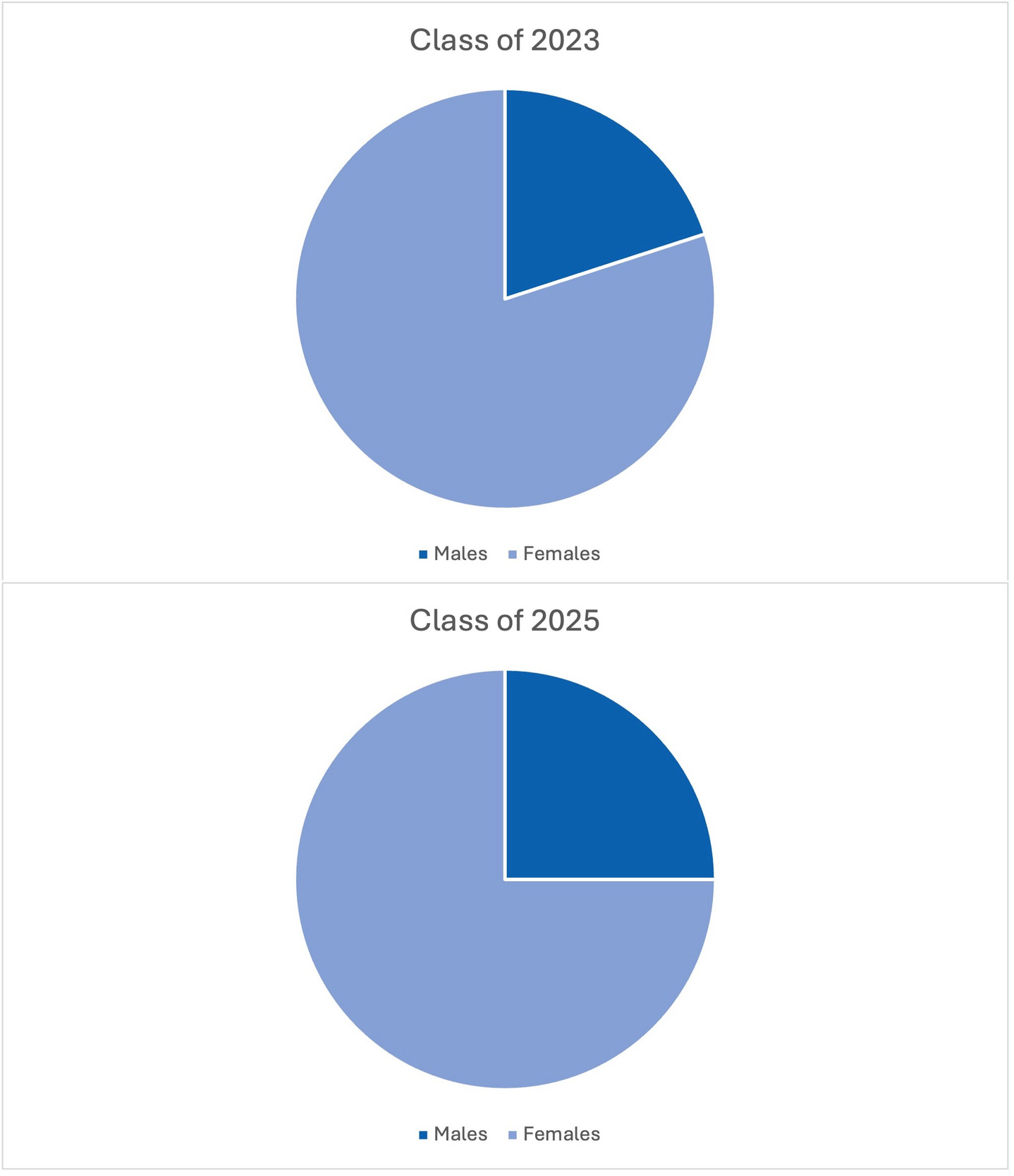

The study included a subject population of 40 graduate students from the nurse anesthesia program: 20 students from the Class of 2023 and 20 students from the Class of 2025. The Class of 2023 is the last master’s cohort, and the Class of 2025 is the first doctoral cohort. The subject population’s gender, years of clinical experience as a registered nurse and specialties are illustrated in Figures 2-4. Participants were able to select more than 1 category for the specialties worked. The researchers conducted recruitment through a class presentation and follow-up email outlining the project and its timeline.

Ethical Considerations

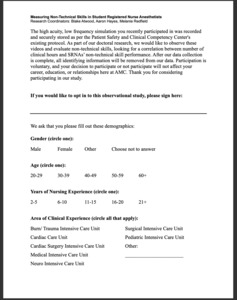

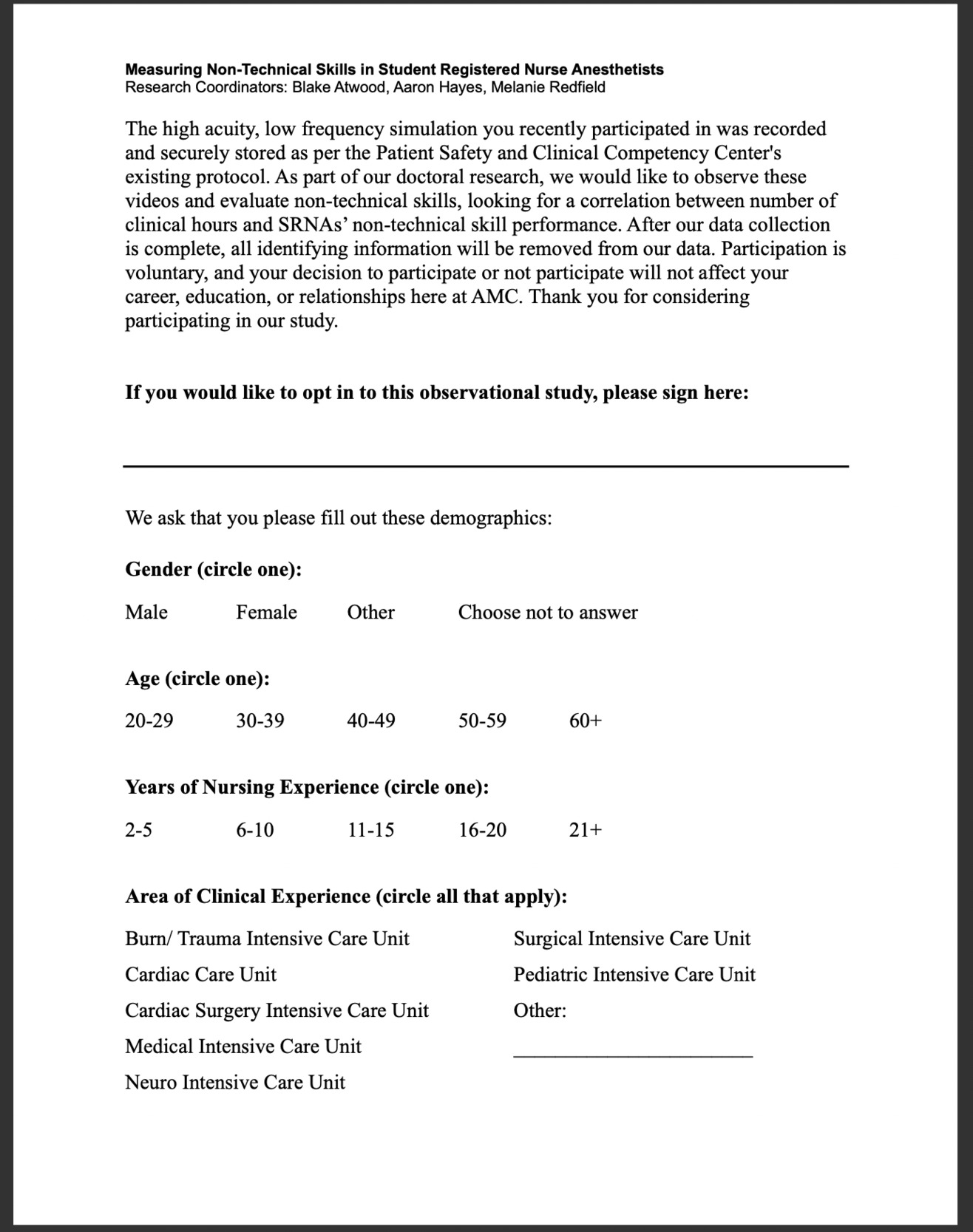

Several measures were implemented to maintain the confidentiality of the participants. These measures included using opt-in forms and ensuring data security through the academic institution’s secure access hard drives. Participants’ performances during the simulation were video and audio recorded, as is standard for all simulation experiences at this institution. Following the simulation scenario, the participants were presented with an opt-in form (Figure 5), which included 4 demographic questions following the SAGER Guidelines. The opt-in form addressed the voluntary nature of the study, highlighting the decision to participate or not as independent from the participant’s future standing within the program or relationships at the institution, and was in accordance with the Belmont Report’s principle of respect for persons.13,14 Opt-in forms were saved on a password-protected computer at the academic institution and all participant identifying information was destroyed after data collection occurred. The nature of the research disallowed eliminating an observer bias between researchers and participants and will be addressed as a limitation.

The Intervention

This research study employed a retrospective evaluation, focusing on the simulation performance of each SRNA. The Class of 2025 served as the relative control group due to their limited amount of anesthesia clinical hours (422 hours) compared to the Class of 2023 (1,170 hours) (Figure 6). The primary objective was to examine the relationship of experience, measured in clinical hours, with ANTS scores in a simulation crisis scenario.

Measures, Tools, and Instruments

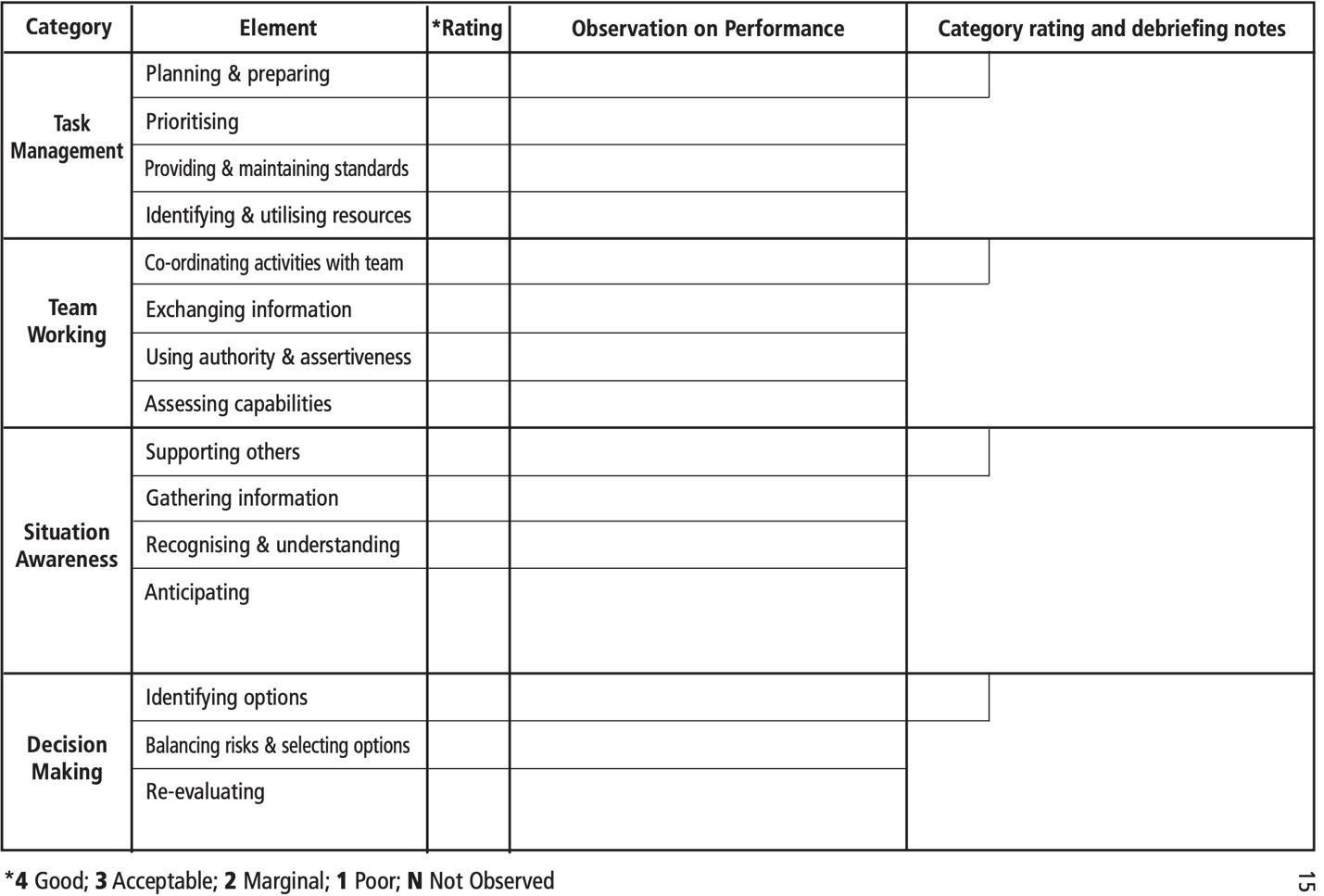

The ANTS tool (Figure 7) uses behavioral markers for each skill and utilizes a rating system to score behaviors. The scale ranges from 1-4, with 1 representing “poor” and 4 representing “good”. There are 4 categories with a total of 15 elements.

Prior to the investigation, evaluators were instructed in the utilization of the ANTS tool. The training included familiarization with the ANTS framework, rating system review, participation in simulation scenarios, and consensus building. Inter-rater reliability was mild to moderate, with Kappa ≥ 0.67. Of note, the effectiveness of the ANTS tool in assessing NTS in the medical field has been demonstrated as valid and reliable.2,5,9,15

A statistician at the academic institution performed raw data interpretation to ensure scientific validity. The data sets were complete with no missing data points. Summary statistics were reported as raw data and ranges. Comparisons were made with t-tests or Mann-Whitney tests depending on the type of distribution for continuous variables. All analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel.

Results

Of the 15 elements, 3 revealed statistically significant results with confidence interval (CI) values ≥95%. The 3 elements were Task Management: Planning and Preparing (p = 0.023), Task Management: Providing and Maintaining Standards (p = 0.036), and Decision Making: Balancing Risks and Selecting Options (p = 0.046). The median score for the Class of 2023 for Planning and Preparing was 3.67, while the median score for the Class of 2025 was 3.00. For the Class of 2023, the medians for Providing and Maintaining Standards and Balancing Risks and Selecting Options (both 3.67) were also significant compared to the Class of 2025 (both median scores 3.00). The median scores for the elements that were considered significantly different are included in Table 1. The Class of 2023, with more clinical hours, achieved higher median NTS scores.

The mean NTS scores for the Class of 2023 were higher in the 4 main categories (Task Management, Team Working, Situation Awareness, and Decision-making) compared to the Class of 2025. Of the 15 elements, 3 revealed statistically significant results. The 3 elements were Task Management: Planning and Preparing (p <0.05), Task Management: Providing and Maintaining Standards (p <0.05), and Decision Making: Balancing Risks and Selecting Options (p <0.05). The mean for the Class of 2023 for Planning and Preparing was 3.52, compared to the Class of 2025 which was 3.10. For the Class of 2023, the mean for Providing and Maintaining Standards was 3.50, compared to the Class of 2025 which was 3.15. For the Class of 2023 the mean for Balancing Risks and Selecting Options was 3.38 while the mean for the Class of 2025 was 2.98. The mean scores for the elements that were considered statistically significant are included in Table 2.

Discussion

Summary of Key Results

There was a correlation between clinical hours and 3 of the 15 elements of the ANTS tool. The statistically significant data demonstrated that as students interface within the clinical setting, NTS scores improved. Additionally, the raw data demonstrated higher performance in every element of the ANTS tool for the Class of 2023 compared to the Class of 2025.

Interpretation

The ANTS tool can be used to evaluate anesthesia practitioners in clinical and simulation settings, offering a platform to identify and measure critical NTS.1 These NTS are critical for optimal outcomes, particularly in high-stress, dynamic anesthesia environments.1 The ANTS tool’s structured utilization ensures comprehensive understanding among assessors, promoting consistency in both assessment conduct and interpretation.1 Finally, the ANTS tool is designed for objective and consistent application across various facilities, countries, and training environments.1

Despite the critical role of NTS in anesthesia practice, there exists a significant knowledge gap regarding how the number of clinical hours among SRNAs influences the development of these skills, especially within a simulation setting. This study explored this relationship by comparing the ANTS scores of the Class of 2023 and 2025, who had differing amounts of clinical hours. The data revealed 3 elements with statistically significant differences between the 2 classes: Task Management: Planning and Preparing, Task Management: Providing and Maintaining Standards, and Decision Making: Balancing Risks and Selecting Options. The Class of 2023, with more clinical hours, consistently achieved higher mean scores in these areas compared to the Class of 2025. Specifically, the median scores for the Class of 2023 in Planning and Preparing, Providing and Maintaining Standards, Balancing Risks and Selecting Options were higher compared to the Class of 2025 in all 3 elements. These findings suggest that increased clinical experience may enhance certain NTS, and a simulation setting provided a non-clinical, low-risk environment for evaluating ANTS scores.

Limitations

The limitations included convenience sampling at a single-site academic institution. The sample size (n = 40) may have been insufficient to capture subtle but statistically significant variations in ANTS scores between the 2 groups. Further exploration with a larger sample size is needed to determine whether the observed differences are truly indicative of clinical experience.

Another limitation involves the potential influence of unconscious biases and the Hawthorne effect on study outcomes. Participants received an email prior to the simulation scenario summarizing the nature of NTS and the research study; there was a risk that participant behavior or responses may have been influenced by the knowledge of being observed. The opt-in forms were completed after the simulation, which may have affected the decision to participate. Additionally, the researchers may have unintentionally introduced biases into the assessment process based on their perceptions or expectations, as the researchers were also SRNAs in the Class of 2025 cohort. Future studies could implement blinding techniques to enhance the validity of the findings.

The generalizability of the findings may be limited by the homogeneity of the sample population and the specific context in which the study was conducted. Participants were drawn from a single-site institution, and the study focused primarily on the number of clinical hours on ANTS scores. As such, the findings may not be fully representative of anesthesia learners in other settings or training programs. To enhance generalizability, future studies could involve a more diverse participant pool drawn from multiple institutions and geographic regions, allowing for broader insights into NTS development and training effects.

Conclusion

The statistically significant differences demonstrated in Task Management: Planning and Preparing, Task Management: Providing and Maintaining Standards, and Decision Making: Balancing Risks and Selecting Options suggest that clinical experience bolsters proficiency in NTS. However, this study is limited by its single-site design and the retrospective nature of the data collection, which may affect the generalizability of the findings.

This study, alongside future research, can significantly contribute to the educational landscape for nurse anesthesiology programs and enhance safe patient care. Future research should explore the longitudinal development of NTS in diverse clinical settings and investigate the impact of targeted NTS training interventions. Additionally, integrating NTS assessment tools like ANTS into regular training and evaluation processes could further improve the proficiency and safety of anesthesia practitioners.