Introduction

Resident Registered Nurse Anesthetists (RRNA) are guided by their clinical preceptors as they acclimate to the clinical environment and transition from didactic education to clinical practice, which is often a new and unfamiliar setting for them. Clinical preceptors who foster personalized and focused attention for RRNAs help them develop clinical skills, competencies, and confidence, which are essential foundations as they enter practice.1–3 Clinical sites that provide high-quality, dedicated preceptors that improve RRNA competency and confidence often experience higher employment retention rates post-graduation.4

L’Ecuyer et al5 reported that 63% of preceptors took preceptorships without formal training or guidance. The absence of a formal preceptor training program (PTP) impedes clinical preceptors’ role competence and impairs effective knowledge and skill transfer to RRNAs. A lack of role clarity leads to organizational inefficiency, inadequate communication skills, inconsistent education quality and mentorship, and medical errors, which can compromise patient safety and outcomes.6–12 Conversely, research demonstrates that participation in PTPs increases the preceptor’s self-confidence, satisfaction, and professional development.13 According to the American Association of Colleges of Nursing, “clinical staff at the practice partner institution should receive comprehensive training or orientation and ongoing support for the clinical preceptor role.”14

This performance improvement (PI) initiative focuses on bridging the gap between clinical preceptors’ current practice and best practices by implementing PTPs across 5 teaching hospitals. The training emphasized 3 key domains: interpersonal/intrapersonal skills and attitudes, knowledge and understanding, and administrative resources and support. The online training featured discussion content, an evidence-based educational platform, high-fidelity trigger films, and 3 learning modules. Key outcome measures included pre- and post-implementation assessments using the L’Ecuyer Preceptor Self-Assessment Tool (PSAT-40) to assess changes in preceptor competency. The PSAT-40 is a validated instrument designed to evaluate the self-perceived competencies of nurse preceptors in clinical education settings.5 Developed by Dr. Kristine M. L’Ecuyer, the tool aims to facilitate the professional development of nurse preceptors by identifying areas of strength and those needing further growth in their roles as educators and mentors. The PSAT-40 development followed a systematic, multi-phased process rooted in theoretical frameworks and empirical research, accompanied by expert peer review, pilot testing, and statistical validation. Based on statistical findings and user feedback, the final instrument was streamlined to 40 items, with 10 items per domain. This version maintained high content validity and internal consistency, supporting its use as a reliable self-assessment measure for nurse preceptors.5 The project’s efficacy was measured through statistical analysis of improvements in overall competency scores before and after formal PTP implementation.

Methods

Framework

Albert Bandura’s social cognitive theory of self-efficacy served as the PTP’s foundational framework. Bandura’s core theory is the concept of self-efficacy, representing an individual’s belief in their capacity to perform tasks and attain desired outcomes.15 Central to competency development is the cultivation of self-efficacy among clinical preceptors as they must possess confidence in their abilities to mentor and guide learners effectively. Utilizing Bandura’s theory, the project involved identifying key learning objectives for preceptors, integrating knowledge assessments, presenting modeling videos, boosting confidence through targeted questions and follow-up discussions, creating a supportive environment, and developing a structured training platform. An evaluation was completed using the PSAT-40 before and after training, supplemented by ongoing educational resources and administrative support. By adopting Bandura’s self-efficacy theory as the framework for this PI project, preceptors had the opportunity to acquire practical skills and knowledge, identify areas for improvement, and enhance their competency and confidence levels.

Target Population and Setting

The participants in this PI initiative were clinical preceptors from 5 teaching hospitals, including community and regional medical centers, a children’s hospital, and level 1 and level 2 trauma centers. The convenience samples were subject matter experts (SME), and participation by SMEs was strictly voluntary. Inclusion criteria were clinical preceptors (also considered SMEs) employed by organizations that precept RRNAs. The exclusion criteria were clinical preceptors who did not want to participate in the PI initiative.

Demographic Measures

Participant demographics were obtained through a short survey. The survey elicited each participant’s years of clinical experience and the time spent precepting clinical residents. No identifiable information about participants was obtained.

Validated Instruments and Measures

The project’s effectiveness was evaluated using the Preceptor Self-Assessment Tool (PSAT-40), developed by L’Ecuyer et al.5 The PSAT-40 encompasses 3 domains, including interpersonal and intrapersonal skills and attitudes (26 items), knowledge and understanding (10 items), and administrative resources and support (4 items) for a total of 40 points that assess a range of preceptor competencies. Each item is rated on a Likert-type scale. Clinical preceptors self-assess across the 3 domains of the PSAT-40 and determine their overall competency score. The tool aims to help clinical preceptors understand expected competencies and identify their strengths and areas for improvement.5 The items on the PSAT-40 were found to have a Scale-Level content validity index (S-CVI) score of 0.90 (0.983). An S-CVI above 0.90 is considered to have excellent content validity.16

Intervention and Data Collection

To maintain anonymity, no personally identifiable information of participants was collected. Meetings were held with the participants at the beginning of implementation to describe the project’s purpose, intervention, and procedures. Within the same week, pre-intervention surveys were emailed to participants describing the project’s purpose, intervention, and procedures. The initial email provided a link to a Qualtrics survey.17 The survey contained the demographic questions and the PSAT-40 questionnaire. Participants had 2 weeks to complete the baseline PSAT-40 assessment. After the second week, an email was sent with a link to the PTP, including a dedicated website designed to administer PTP content. This platform included educational resources about the 3 domains of the PSAT-40. Integrated trigger videos presented effective and ineffective preceptor behaviors, followed by thought-provoking questions and educational discussions. Participants were asked to complete the training in 1 week but had access to the PTP for reference if needed. Participants then incorporated the knowledge gleaned from the PTP into their clinical practice. Participants received email reminders for 1 and 2 months after accessing the PTP website. Three months later, a post-evaluation of the PTP was conducted via a Qualtrics questionnaire of the PSAT-40 distributed to all participants via email. The timeline from initiation to completion was 3 months.

The pre-and post-questionnaires sent via Qualtrics for each domain were password-protected. The data collected, verified for accuracy and completeness, was exported from Qualtrics and imported to SPSS 29 software. The data imported was encrypted on a file within SPSS 29 and only accessible with a password by the PI initiative team members.

Data Analysis

Analyses were performed with SPSS 29 software.18 Project effectiveness focused on outcomes-based performance measures, particularly enhancing the overall total competency courses post-PTP implementation. Project effectiveness was measured by comparing pre- and post-test scores for the PSAT-40. The 40 items on the PSAT were measured on a 5-point Likert scale of 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree or disagree, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree.5 The pre-test and post-test comparisons for the PSAT were performed on each of the 40 individual items; participants were asked to assign a score based on the content of the question. The total score means that the averages for the pre- and post-test were analyzed using t-tests and statistical analysis of the mean scores. Alpha <0.05 for all inferential tests was considered a significant difference. Total competence scores range from less than 50 to greater than 150, with a score less than 50 indicating beginner, 51 to 100 indicating intermediate, 101 to 150 indicating advanced, and greater than 150 indicating proficiency.

Ethical and Legal Considerations

Few ethical and legal considerations exist for this PI initiative, as the type of data collected from this initiative does not involve patients or protected health information and does not encompass personal information. The study did not involve human subjects research, yet a request for review was initiated with the University of South Florida’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) and various hospitals’ IRBs before proceeding. The project received IRB exemption based on its design. Participation in this project was voluntary and declining to participate in any or all of the PI initiative’s activities did not negatively affect staff. Confidentiality was the most significant legal and ethical concern for this intervention, as the tool used to measure the outcome (PSAT-40) requires the participant to evaluate administrative, managerial, and institutional support.5 The participants’ identities were protected because participants are not required to enter identifiable information for participation in this project. All data was securely stored in the Qualtrics survey in the cloud, protected by 2-factor authentication. This data was deleted at the end of the PI initiative.

Results

The data support evidence for PTPs that emphasize implementing learned skills into practice can improve overall preceptor competence. See Table 1 for a summary of preceptor skill and scoring systems.

Demographics

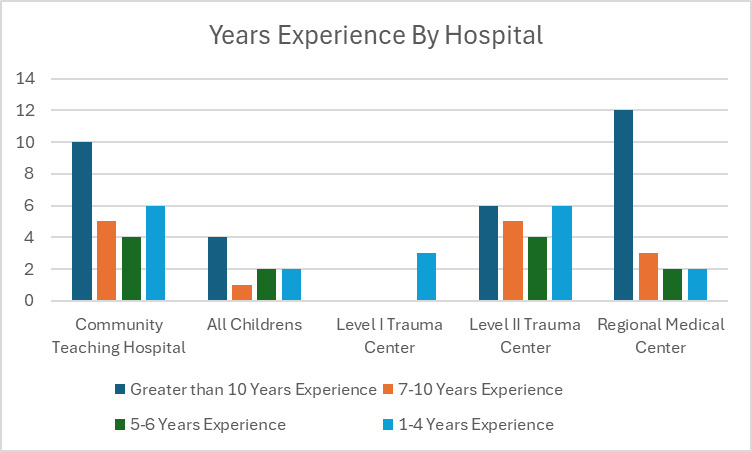

Not all participants completed the demographic survey; however, among the 75 who did, 28 had over 10 years of clinical anesthesia experience, 14 had 7-10 years, 11 had 5-6 years, and 22 had 1-4 years (see Figure 1).

Pre-Implementation

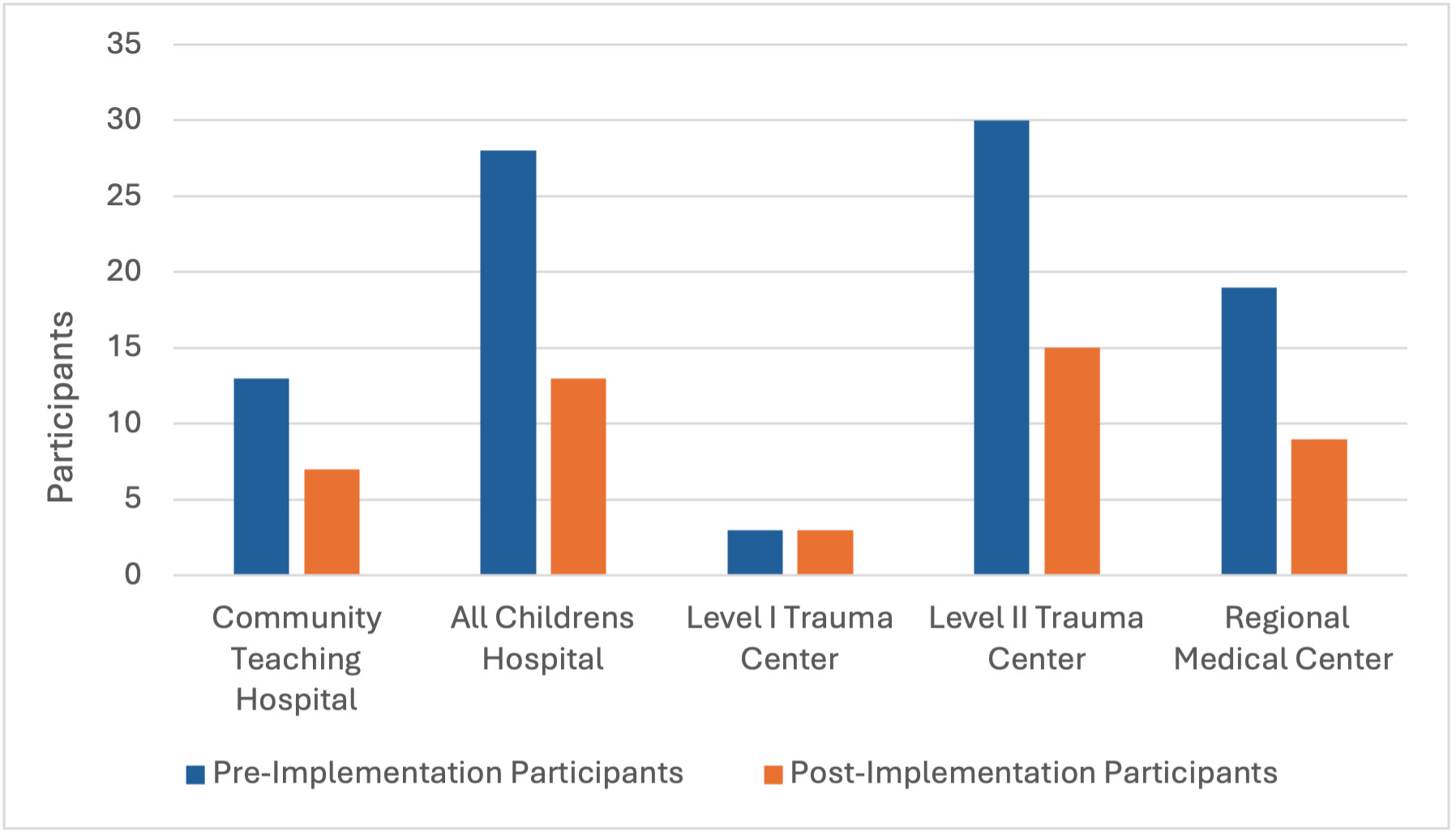

Of the 93 participants who precept RRNAs across the 5 area hospital systems, 93 completed the pre-test PSAT-40 (100% response rate). For the total competency score, 3 participants scored as advanced (101-150) and the remaining 90 as proficient (>150). The pre-implementation PSAT-40 maintained excellent reliability and consistency with Cronbach’s α = 0.96.

Post-Implementation

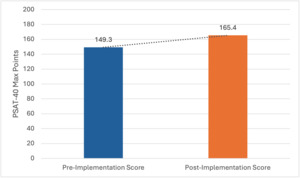

Of the 93 participants who completed the pre-test, 47 completed the post-test following implementation of the PSAT-40 and all requirements (50.53% response rate). Participants who failed to complete the pre- and post-implementation questionnaire criteria were excluded from the dataset, resulting in a final sample of N = 47. The total scores increased from a median pre-implementation score of 149.3 to a median post-implementation score of 165.4, out of the maximum of 200 possible points on the PSAT-40, indicating increased proficiency of 8% for preceptors who completed the training program. Following implementation, the PSAT-40 maintained excellent internal reliability and consistency, as indicated by Cronbach’s α = 0.955. Figure 2 presents the number of participants at each hospital pre- and post-implementation, while Figure 3 illustrates the percentage improvement from pre- to post-implementation across all participants at the 5 hospitals.

Discussion

The PTP aimed to empower clinical preceptor participants with essential inter/intrapersonal skills such as delivering constructive feedback, fostering effective communication, implementing early problem-solving strategies, and understanding administrative resources and support for conflict resolution. This program was designed to equip clinical preceptors with knowledge and tools to prepare them for their roles. The online format of the PTP allowed clinical sites to sustain the program beyond its initial implementation by providing a cost-effective, accessible, and easily updatable training platform that can be shared with new clinical preceptors of RRNAs. This ensured that the knowledge and resources gained from the program could be perpetuated, contributing to the ongoing professional development of clinical preceptors and benefiting patient care in the long term.

This PI initiative could impact patient outcomes positively by improving role clarity for the clinical preceptors. This potentially leads to increased job satisfaction, retention of providers, and overall improvement in patient safety. Patient care indirectly benefits from improved clinical preceptorship and effective clinical preceptor training. Future PI and quality improvement initiatives investigating the importance of clinical preceptor training and development should seek out clinical preceptors with limited precepting experience to improve early competence. Additionally, methods that could improve the integrity and efficacy of future initiatives should be considered. These methods include, but are not limited to, mandating participation to ensure sufficient sampling, extending the implementation period to allow more time for the adoption of changes and opportunities to precept, and creating a distribution method that retains anonymity yet allows for monitoring participant interaction with educational modules.

Limitations

The identified limitations of this PI initiative were that 93 clinical preceptors initially accessed the link and started the PTP. However, only 47 completed the entire training and post-implementation PSAT-40, which decreased the sample size. Another limitation was that not all participants in the preceptor training reported demographics such as years of experience as a practitioner. Due to the voluntary nature of this PI initiative, sample bias was a limitation, likely attributed to the possibility that participants were limited to those already interested in clinical precepting.

The consistency of results was also limited due to de-identification to maintain anonymity. This prevented tracking pre- to post-implementation changes on an individual basis. The distribution of this PI initiative was another limitation. It was openly distributed via e-mail, with no way to verify that participants who completed the pre-implementation questionnaire were the same participants who completed the post-implementation questionnaire. Furthermore, ensuring accountability in viewing the educational material was impossible, which may have affected the post-implementation results. Another limitation was the inability to ensure or verify consistent precepting opportunities for participants, which may have limited the participants from implementing changes in preceptor practice. Lastly, this PI initiative was conducted at several sites, which may have affected the sample population and the generalizability of the study.

Conclusion

Despite these challenges, this PI initiative demonstrated that a formal PTP can enhance clinical preceptor practices, foster professional growth, and improve the overall quality of mentorship and education for RRNAs. Future iterations of the program could benefit from redesigning the questionnaire to make all questions mandatory to ensure more complete responses and reduce the number of responses discarded due to missing information. A numerical system should be added to help monitor both portions’ completion, ensure completeness, and increase surveyor responses. Other considerations include increasing clinical preceptor participation by engaging a larger sample size and implementing incentives earlier in the project. This would further help close the gap between clinical preceptors’ current and best practices.

Acknowledgement

The authors sincerely thank Dr. Kristine L’Ecuyer for her invaluable contribution to nursing education through the development of the Preceptor Self-Assessment Tool, now in its final form as the PSAT-40. Dr. L’Ecuyer’s work has established construct validity and reliability for this instrument, which serves as a meaningful tool to assess preceptor competency. The PSAT-40 enables nurse educators to identify the developmental needs of preceptors and design targeted educational initiatives that strengthen preceptorship and support excellence in clinical teaching.