Introduction

The Critical Need for Structured Clinical Communication

The ever-increasing complexity of healthcare delivery has subsequently increased the need for effective communication to sustain high-quality patient care. Communication breakdowns represent a significant threat to patient safety. Structured reviews note that hand-off failures and ambiguous exchanges contribute to most sentinel events and medical errors.1,2 In fact, the Institute of Medicine’s To Err Is Human report2 estimated that tens of thousands of preventable deaths occur annually in U.S. hospitals due to medical error. Poor communication is particularly problematic during care transitions, handoffs, and in high-acuity settings where accurate information sharing is essential for patient outcomes.1,3 For instance, observational studies in operating rooms have identified frequent and recurrent patterns of communication failure, such as omissions, timing errors, and misunderstandings that disrupt workflow and compromise safety.3 In response to these risks, the Joint Commission and other healthcare entities have issued calls to action, recommending standardized hand-off protocols to improve clinical communication.4,5 Despite these initiatives, evidence demonstrates that healthcare professionals, particularly those in training, often struggle with clear, structured communication.5 Communication is particularly challenging for trainees because of various factors, such as frequent distractions, differing communication styles among professionals, cultural and workforce diversity, variations in education levels, physical and mental demands, and workload time pressures.

According to accreditation and professional standards within nurse anesthesiology, residents are required to compose a written or verbal care plan for each case. However, explicit instructions concerning the makeup or presentation of these care plans do not currently exist. Therefore, the development of a formalized method to approach care plans would serve to ensure that residents meet professional expectations and requirements for every case.

Traditional clinical education often lacks formal training in structured verbal reporting and care plan presentation.6 This gap between educational preparation and clinical practice requirements can lead to preventable medical errors, delays in care, and compromised patient safety.7,8 Updated requirements by accrediting bodies have begun to address this disparity in training.9,10 Educators must now explore effective methods to implement these changes into the curriculum. Aside from becoming consistent evaluators, educators must also determine best-evidence strategies to teach professional communication.

Prior to entering clinical practice, strategies using simulation-based training aid in guiding and developing competency in communication.11,12 This time of transition, which exhibits high levels of stress and disorientation experienced by trainees, often referred to as “Reality Shock”,13,14 is a particularly vulnerable period for communication errors. Role-play simulations involving scenarios have demonstrated efficacy for increasing effective communication.15–17 Of interest to educators is that these simulations are low-stakes practice opportunities capable of being standardized and repeated for consistency. These simulations are meaningful for learners as evaluators can offer immediate feedback. Using simulation to guide learners is essential since time to practice communication in the clinical arena is limited, preceptors may lack formal communication coaching, and feedback on performance is often inconsistent.

The Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation (SBAR) is an established evidence-based framework for standardizing clinical communication.18–21 Originally developed by the military and adapted at Kaiser Permanente, SBAR provides a structured approach for organizing and conveying critical patient information.12,14 The framework includes the situation (current patient status), background (relevant clinical history and context), assessment (analysis of the problem), and recommendation (suggested actions/plan). The effectiveness of this approach is demonstrated for a multitude of reasons, particularly in reducing medical errors.1,21,22 Research specific to simulation-based SBAR training demonstrates increased confidence in communication, enhanced clarity, and improved completeness of information presented. However, in anesthesia settings, which require anticipatory reasoning and strategic planning, the linear structure of SBAR may not fully support the needs of anesthetic care planning.

A New Framework

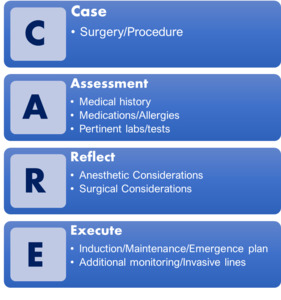

Preoperative planning between an anesthesia resident and a preceptor is a time of critical information exchange and meticulous strategizing. While SBAR is effective across many clinical contexts, its structure does not fully support anticipatory reasoning, collaborative decision-making, and strategic formulation. Due to the forward-looking and analytic nature of anesthetic care planning, the SBAR technique does not precisely meet the needs of the dynamic interaction between the preceptor and preceptee at the pivotal time in patient care planning. To address this gap, the CARE framework was formulated by adapting from SBAR to meet the needs of the preceptor and preceptee. The authors developed the framework by systematically reviewing established professional standards for perioperative care and documentation and distilling these elements into consolidated categories. The elements were subsequently organized into a simplified, acronym-based framework to promote efficient recall and facilitate clinical application. The CARE framework as seen in Figure 1, guides practitioners through presenting the Case (surgical details); review the initial patient Assessment (medical history, medications, and pertinent labs or tests); Reflect upon surgical and anesthetic considerations; and outline the Execution plan (intended interventions, monitoring, and techniques). As is evident, the CARE framework, was specifically tailored to facilitate preoperative planning and communication between nurse anesthesia residents and preceptors. In these settings, rapid decision-making and complex interventions are routine, so adopting a structured communication approach enhances the educational experience for learners.15,23–25

Methodology

The aim of this study was to determine the effectiveness of training for and utilizing the CARE acronym-based communication framework on nurse anesthesia resident reported confidence. Particular emphasis was placed on assessing ideal behavioral markers for non-technical skills, including task management, team working, situation awareness, and decision making.24 Specifically, perceived self-confidence of the resident learner was evaluated to gain initial insight into the effectiveness of the CARE framework-guided simulation.

Design

This study utilized a pre-experimental, single-group pretest–posttest design to evaluate the impact of CARE framework communication training and simulation on self-reported confidence among nurse anesthesia residents. All participants completed identical pre- and post-intervention surveys immediately before and after the simulation. No control group was included. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained, and all ethical requirements were followed throughout the study.

Training in the use of best-evidence resources, anesthetic plan development, and verbal presentation skills within the CARE framework was delivered in a single, structured 90-minute instructional session. The session also addressed the identification of professional standards for anesthetic care plans, provided a detailed explanation of the CARE framework’s design, and included a practical discussion on strategies for maintaining its clinical relevance. Participants were then given a random patient case scenario, which included a complex makeup of the patient’s medical history, preoperative labs and testing, and the intended surgical need. They were then given approximately 45 minutes to prepare an anesthetic plan in order to implement their training. Upon completion of the preparation, the student was invited to present their plan using the CARE-based method. The role-playing simulation occurred within a high-fidelity operating room with faculty evaluators serving as the preceptor. Students were evaluated formatively using a met/unmet assessment by faculty, guided by a rubric aligned with the objectives of the CARE framework. Following the evaluation and debriefing, students were offered feedback from faculty members in order to review any strengths or weaknesses of their presentation.

Sample & Setting

The sample consisted of 29 nurse anesthesiology residents enrolled in an accredited sequential didactic-clinical curriculum graduate program who had completed the didactic phase of their training and were preparing to enter clinical residency. Participants were selected using computer-generated random sampling from a larger eligible cohort. Invitations were distributed via email, and participation was voluntary, with the option to withdraw at any time. A total of 35 students were invited to participate based on consideration of faculty schedule, anticipated attrition, and feasibility considerations for pilot evaluation. Six students declined to participate, resulting in a final sample of 29, all of whom completed the simulation and both the pre- and post-intervention surveys.

Data Collection

A pretest and posttest were obtained from a questionnaire that was made available via an electronic tablet. The questionnaire was developed to parallel the practice-based sequence of planning to reflect clinical expectations while still integrating the principles of the CARE framework. The students rated their confidence on a 5-point Likert scale through a series of 5 questions, which assessed aspects of verbally presenting an anesthetic care plan. The 5-point Likert scale scored from 1 (concerned) to 5 (confident). Question domains consisted of self-rating confidence in utilizing resources pertinent to care planning (Q1), prioritizing relevant information when planning (Q2), formulating a plan that meets professional expectations (Q3), presenting a verbal care plan to a preceptor (Q4), and exchanging information in coordination with preceptor feedback and questioning (Q5). An optional open-ended item invited participants to provide feedback or recommendations pertaining to the simulation. No demographic or identifying information was obtained in order to reduce possible bias and increase participant privacy. The participants were allowed to complete the survey in a location separate from researchers in order to increase privacy and remove potential for undue influence.

Analysis & Results

The collected data was input into JASP (version 0.19.2) to perform all descriptive and inferential statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics for each item on the questionnaire, including mean, median, mode, and standard deviation, are presented in Table 1. Pretest scores demonstrated moderate variability across items, with mean scores ranging from 2.48 to 2.93. Posttest scores showed improvement across all items, with mean scores ranging from 3.66 to 3.97. This indicates a consistent increase in confidence following the intervention. Paired-sample t-tests were conducted, and assumptions of normality were assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Several items violated the assumption of normality (p < .05); therefore, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were additionally employed as nonparametric alternatives. Despite normality violations, both t-tests and Wilcoxon tests indicated notable enhancements from pretest to posttest. To further examine the magnitude and precision of the observed changes, 95% confidence intervals for the mean were calculated using the bootstrap method, given the previously discovered non-normality. These calculated intervals support the conclusion of positive change. The normalized gain formula was applied to compute an effectiveness index for each item, with values ranging from 0.43 to 0.57, indicating moderate to relatively high effectiveness. To assess internal consistency of the questionnaire, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated, resulting in values of 0.85 for the pretest and 0.96 for the posttest, which reflect excellent internal reliability of the instrument. See Figures 2 and 3. Overall, the reliability of the measures was robust, and the findings were consistent across parametric and non-parametric analyses.

Study Limitations

Despite the findings of this study, there are several limitations worth acknowledging and considering in the conclusions of the results. The sample size of a single cohort was small and limited to a single institution. Despite the potential of being an underpowered study given participant attrition, the magnitude of the intervention proved effective enough to demonstrate significance. The study employed a single-group, pre-post design without a contemporaneous control arm. In the absence of a comparator, observed improvements cannot be unequivocally attributed to the intervention and should instead be considered causal in effect. Outcomes were limited to participants’ perceived self-confidence, captured via a single self-report instrument. Although confidence is a relevant precursor to performance, self-assessment is vulnerable to social desirability and recall biases, and it may not correlate linearly with objective competence. Data was captured immediately post-intervention, precluding any assessment of skill decay or sustained behavioural change. In short, because the investigation lacked a control group and relied exclusively on short-term, self-reported confidence metrics, causality and clinical translatability remain uncertain.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the intervention significantly improved participants’ confidence across all measured items. Both statistical and practical significance are evident by percentage improvements in correlation with significant p-values. These findings align with a growing body of literature underscoring the value of structured communication tools in medical and nursing education. In addition to the quantitative analytics, open-ended feedback responses included on the post-intervention survey were positive as related to participant experience and overall simulation design. The consistency of qualitative findings further reinforces the statistical findings offered. Unrelated to the purposes of this study, but worth mentioning is that many participants commented that the timing of the simulation was advantageous, as it created an opportunity for precursory evaluation of the ability to apply and critically think through realistic scenarios just prior to entering clinical residency. Information from student performance in these simulations can offer high-yield insights to both the program faculty who seek to evaluate retention of foundational knowledge and for the students to determine confidence in clinical readiness as they progress into residency.

The findings of this study support CARE as a viable framework, which is a tailored alternative that addresses the unique needs of anesthesiology education. Its structure accommodates the anticipatory and preemptive planning dynamics involved in anesthesia practice. Previous formats, such as SBAR and the adjusted ISBAR or the alternative I-PASS, were originally intended to serve as handoff tools. As such, those tools were designed to be static to match the intended reporting purposes between healthcare practitioners. The CARE framework, meanwhile, encourages prospective articulation of clinical strategy, better suiting the educational context of anesthetic planning between anesthesia residents and preceptors.

The item that reflected the greatest improvement among participants involved the primary objective of the framework, which was increasing confidence in verbally presenting to a preceptor. This suggests that the model may be especially effective in cultivating not just internal confidence, but also interpersonal communication behaviors that translate directly into clinical performance. This aligns with findings from Farzaneh et al,18 who observed similarly strong improvements in self-efficacy and clinical decision-making among anesthesiology nursing students following SBAR-based simulation. However, while their intervention spanned 8 sessions over 4 weeks, the current study achieved comparable gains through a single structured session, suggesting the CARE framework may yield efficient learning outcomes when tailored to its domain. Preparing students to manage preceptor interactions with structured communication tools not only builds confidence but also promotes more favorable preceptor perceptions during the early stages of clinical immersion. This further supports simulation-based CARE framework training as a valuable bridge between theory and practice.

From a pedagogical standpoint, the use of simulation, immediate feedback, and role-playing within a high-fidelity environment likely contributed to the effectiveness of this intervention. Simulation has consistently demonstrated improved communication, critical thinking, and decision-making skills. Unlike prior studies focused on general communication or handoff safety, the CARE framework targets anesthetic-specific planning behaviors, offering a discipline-specific advantage not yet addressed in the literature.

Future Research

The preliminary findings of this study, which demonstrated promising improvements in nurse anesthesia residents’ self-reported confidence, provide a foundation for further exploration of the CARE. To build on these results, future research should address several key areas to validate and extend the framework’s utility in anesthesia education and beyond.

Longitudinal studies are essential to assess the durability of the observed confidence gains and their translation into sustained behavioral changes in clinical practice. The current study captured data immediately post-intervention, limiting insights into skill retention over time. Future investigations could implement follow-up assessments at intervals (e.g., 3, 6, and 12 months) during residents’ clinical training to evaluate whether CARE-based training maintains its impact on communication skills. Such studies could also explore whether repeated exposure to CARE-guided simulations enhances retention, potentially reducing the “reality shock” experienced during the transition from didactic to clinical environments. Elucidations of this sort would provide additional validity to the design of the simulation and timing within anesthesia training programs.

Incorporating preceptor-rated outcomes would provide a more objective measure of the CARE framework’s effectiveness and match the long-term goals intended as part of simulation in healthcare. While the current study relied on self-reported confidence, which demonstrated improvement, self-assessment may be influenced by biases such as social desirability. Preceptor evaluations, using tools like the Anaesthetists’ Non-Technical Skills framework, could assess residents’ ability to prioritize critical information and articulate anesthetic plans in real clinical settings.24 These ratings could validate whether the confidence gains translate into observable improvements in intraprofessional communication and decision-making.

Future research should explore clinical performance metrics to determine the CARE framework’s downstream effects on patient care and operational efficiency. The study’s focus on the communication framework aligns with prior literature linking structured communication to reduced medical errors. Investigating metrics such as error rates, time to complete preoperative planning, or perioperative adverse event rates could establish whether CARE framework training contributes to safer, more efficient care. For example, observational studies in operating rooms could quantify communication-related disruptions before and after CARE framework implementation, building on the study’s finding that CARE enhances information prioritization.

Evaluating the CARE framework in interprofessional and interdisciplinary settings would broaden its applicability and address gaps in external validity. The current study was limited to a single cohort of nurse anesthesia residents, but anesthesia practice often involves collaboration with surgeons, nurses, and other healthcare professionals. Testing the CARE framework in interprofessional simulations, such as those involving surgical teams or critical care units, could assess its effectiveness in facilitating team-based communication and planning. Additionally, adapting CARE for other disciplines, such as surgical or emergency medicine training, could leverage its anticipatory and strategic structure to enhance communication across high-stakes healthcare contexts. These studies could compare CARE to other frameworks (e.g., ISBAR, I-PASS) to determine its relative efficacy in diverse settings.

In summary, future research should prioritize longitudinal assessments, preceptor-rated outcomes, clinical performance metrics, and interprofessional applications to validate and expand the CARE framework’s role in healthcare education. These efforts would clarify whether the observed improvements in communicative confidence translate into meaningful clinical outcomes, potentially positioning CARE as a scalable tool for enhancing patient safety and training efficiency.

Conclusion

This pre-experimental investigation provides preliminary evidence that the CARE acronym–based framework produces statistically and educationally meaningful gains in nurse anesthesia residents’ self-perceived communicative confidence. Mean Likert scores improved by 0.73–1.18 points across all domains, yielding moderate-to-high normalized gains and large within-subject effect sizes. These results extend the growing body of literature on structured communication tools by demonstrating that a discipline-specific framework, purpose-built for anticipatory anesthesia planning, can be efficiently assimilated at the critical transition point from didactic to clinical training.

From a pedagogical perspective, the combination of mnemonic scaffolding, deliberate practice in a psychologically safe environment, and real-time debriefing appears to accelerate the development of non-technical skills. Notably, the intervention strengthened participants’ ability to prioritize critical information and coherently articulate anesthetic plans to preceptors, both of which are fundamental to safe perioperative care. In curricular terms, CARE framework offers educators a low-resource, reproducible strategy that aligns with accreditation imperatives for explicit instruction in professional communication.

Interpretation of these findings must remain circumspect since confirmation of hypothesized benefits through rigorous, controlled research remains to be determined. The present study indicates that the CARE framework is a feasible and effective educational intervention for enhancing structured communication in nurse anesthesia training. By extension, this method may prove essential to safeguarding perioperative patient safety. In aggregate, the magnitude and consistency of the observed improvements suggest that CARE is a viable framework that merits further investigation.