Over the last several decades, the use of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has expanded in various medical specialties, including anesthesiology.1–3 As an established technology with increasing utility, the value of POCUS in anesthesia has become abundantly clear. POCUS has been discussed and presented at multiple nurse anesthesia conferences and is now being incorporated into the curriculum standards for nurse anesthesia educational programs.

POCUS is cost-effective and quick to implement, making it ideal for use in the perioperative period.4 It can provide valuable diagnostic information, facilitating clinical decisions or assisting with procedural and therapeutic tasks.3 When properly performed, POCUS exams are as accurate as more traditional and expensive diagnostic studies, making them a valuable tool across resource settings.5–7

POCUS is emerging as a key skill that can be used by Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists (CRNA) to guide patient care. In the United States, nearly 59,000 CRNAs provide more than 50 million anesthetics annually.8 In rural clinical settings such as critical access hospitals, CRNAs represent 80% of the anesthesia workforce.8 Such facilities are unlikely to have abundant resources, further elevating the need for a POCUS-trained anesthesia provider. The American Association of Nurse Anesthesiology (AANA) has recognized the increasing importance of POCUS and, in November 2020, released the practice considerations document “Point-of-Care Ultrasound in Anesthesia Care.”3 This document affirmed that POCUS competency is a “critical and core skill” every CRNA should possess.3 The Full Scope of Practice Competency Task Force also identified POCUS skills necessary for new graduates to become autonomous providers. In March 2021, the Council on Accreditation of Nurse Anesthesia Educational Programs (COA) added a requirement for tracking actual and simulated POCUS experiences separate from vascular access.9,10

The primary aim of this study was to assess the current state of POCUS education within CRNA training programs. Specifically, we sought to identify educators’ perceived competencies, current teaching practices, methods of student competency assessment, and barriers to effective training in POCUS. By systematically evaluating these components, the study aims to highlight the critical need for standardized curricula and assessment rubrics aligned with the AANA and COA standards for education and scope of practice.

Review of Current Literature

The literature was searched using PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature, and Google Scholar electronic databases. Terms included in the search were “point of care ultrasonography”, “POCUS”, “Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist”, “CRNA”, “Anesthesia”, “anesthesiology”, “training”, “curriculum”, and “survey”. These terms were combined with the Boolean operators “AND” / “OR”. The websites of related professional associations, including AANA, COA, American Society of Anesthesiologists, and the American Nurses Association, and the bibliographies of relevant articles were also searched. Studies met the inclusion criteria if they were written in English, published in peer-reviewed journals, and reported on POCUS education specific to anesthesia education.

POCUS in Graduate Medical Education and Residencies

The integration of POCUS into graduate medical education has gained significant momentum, particularly within emergency medicine and critical care specialties.11–14 These fields have incorporated POCUS into residency training programs to enhance diagnostic accuracy and procedural guidance. Pilot studies combining online modules with hands-on training improved residents’ knowledge, comfort, and clinical use of POCUS.15,16

Hands-on learning has been incorporated into numerous POCUS curricula with reported benefits to learners. Baylor College of Medicine developed a 3-week curriculum for first-year anesthesiology residents for introductory POCUS in an anesthesiology residency program in 2022, combining lectures and hands-on learning.16 Their structured program significantly boosted knowledge and user confidence in ultrasound applications, including lung, cardiac, and vascular imaging. Similarly, Blackmore et al’s scoping review confirmed that curricula with dedicated hands-on sessions and boot camps outperform traditional apprenticeship models.17 However, both studies highlight the need for standardized evaluation methods and long-term follow-up. An additional survey of anesthesiology programs nationwide uncovered wide variability in training structures. Key barriers included a lack of faculty expertise and limited institutional resources, reflecting the fragmented nature of POCUS integration across undergraduate medical education.18

POCUS in Nurse Practitioner and Physician Assistant Programs

The expansion of POCUS into Nurse Practitioner (NP) and Physician Assistant (PA) training has gained traction, though variability in curriculum quality persists. Some programs offer comprehensive training with simulation and clinical application, while others provide minimal exposure. A narrative review of NP programs stressed the need for national guidelines to standardize ultrasound education and competency expectations.19 In PA education, the inclusion of structured POCUS training has led to increased student confidence and skill.20 Students trained in ultrasound are more likely to use it during rotations and early practice, especially in fast-paced settings where rapid diagnosis is crucial.20

POCUS in Nurse Anesthesiology Education

POCUS is particularly valuable in nurse anesthesiology for procedures such as vascular access and regional anesthesia. However, formal POCUS education is not yet universal across CRNA programs. A national survey found that only 17% of programs offered structured rotations.21 Barriers include limited faculty training, insufficient access to equipment, and curriculum overload. Recognizing its clinical importance, COA mandated POCUS training for all students entering programs after January 1, 2022. Emphasis has been placed on applications like gastric ultrasound to assess aspiration risk. Targeted gastric assessment instruction improved residents’ knowledge and technical performance, highlighting the importance of dedicated POCUS modules in CRNA training.22

Teaching Modalities and Assessment

Effective POCUS instruction requires both theoretical and practical components. Studies consistently show that learners benefit most from hands-on, simulation-based training. However, challenges remain in evaluating competency. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education mandates proficiency in image acquisition and interpretation, but standardized assessment tools are limited. Many faculty lack the confidence to teach and assess POCUS, which undermines program effectiveness.23 Faculty development and certification may be necessary to close this gap and ensure consistent evaluation of learners.23

Most existing literature focuses on training techniques, perceptions, and barriers to POCUS education in medical anesthesiology training programs. Existing validated instruments from anesthesiology and medical education literature were used to guide the development of our survey to assess POCUS in the nurse education setting. Our survey aimed to assess nurse anesthesia faculty’s education and comfort with teaching POCUS, the current state of teaching practices and methods assessments in CRNA programs, POCUS competencies nurse anesthesia educators believe should be taught, and perceived barriers to effective training of Nurse Anesthesia Residents (NARs).

Methodology

Study format

This study employed a mixed-methods, cross-sectional survey design aimed at exploring the current educational landscape of POCUS instruction among CRNA educators. The methodology incorporated both quantitative and qualitative components to provide a holistic understanding of educator experiences and institutional practices. The 2 main components of the study were the survey phase and the focus group phase. The study was first reviewed by the Middle Tennessee School of Anesthesia Ethical Conduct and Review Committee and then sent to the Institutional Review Board Services, where it was deemed exempt. The survey was administered in-person to attendees of the Assembly of Didactic and Clinical Educators (ADCE) conference February 24-26, 2023, and findings were reviewed with focus groups during the ADCE conference in 2024. This conference event was chosen for the study because it is predominantly attended by CRNAs in academia, including program directors, faculty, and clinical instructors. Participants were asked to scan a QR code, which directed them to a Microsoft Forms survey (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). To encourage participation, survey takers were incentivized with a $5 gift card at the completion of the survey.

Focus group participants were recruited via in-person contact at the ADCE conferences held in February 2024 and February 2025. To facilitate easy and anonymous access to the survey, a QR code was prominently displayed on printed flyers and researchers’ digital devices during session breaks and in the exhibit hall. Prior approval from the AANA was obtained.

When scanned using a mobile device, the QR code directed participants to a secure, web-based survey. The survey was anonymous; no names, emails, IP addresses, or identifying metadata were collected. Participants were informed that their responses would be used for research purposes only and that completion of the survey implied consent. The use of a QR code provided a user-friendly and efficient method for data collection, particularly suited to reaching busy clinical educators and program directors in various settings.

Survey Development

Following a focused literature review on POCUS education in anesthesiology and nurse anesthesia training programs, we developed a mixed-methods, exploratory survey to examine the current landscape of POCUS instruction. A 24-item survey was developed based on a synthesis of existing validated instruments from anesthesiology and medical education literature.23,24

The research aims were to investigate:

-

The current level of competency in POCUS skills among nurse anesthesia educators

-

The existing POCUS teaching practices in CRNA programs

-

The current methods used to assess student competency in POCUS

-

The perceived barriers to effectively train NARs in POCUS

-

Educators’ perceptions of the importance of specific POCUS competencies

-

Educators’ suggestions for improving the structure and delivery of future POCUS training programs

The survey specifically focused on the following core POCUS applications:

-

Vascular access

-

Gastric ultrasound (GUS)

-

Abdominal ultrasound for free fluid

-

Lung assessment

-

Airway assessment

-

Inferior vena cava (IVC) assessment

-

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE)

-

Optic nerve sheath diameter (ONSD) measurement for suspected increased intracranial pressure

These procedures were selected based on their prevalence in literature, reported clinical relevance, and endorsement by expert consensus as core competencies for anesthesia providers.

The survey was pilot tested by a panel of 5 CRNA faculty members for content validity, clarity, and relevance. Revisions were made to ensure contextual applicability to nurse anesthesia education. The survey comprised various question formats to capture comprehensive data: Likert-scale ratings, multiple-choice questions, ranking items, and open-ended prompts. Quantitative data derived primarily from Likert-scale ratings and multiple-choice responses were analyzed statistically to identify significant trends and instructional gaps. Qualitative data from open-ended responses were analyzed separately using thematic content analysis, elucidating the underlying barriers and educator perspectives.

Focus Groups

While the initial survey focused on surface ultrasound modalities commonly taught in anesthesia training programs, transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) was added to our list of focus areas after the survey phase, based on new developments in the field. Over the first year of our investigation, we observed a marked increase in the number of conference presentations, professional recommendations, and institutional demands for basic TEE competency, particularly in perioperative and critical care settings. These emerging trends were discussed during our follow-up focus group sessions and prompted us to expand our educational framework to include introductory TEE principles and image acquisition, even at a basic observational level for NARs.

To contextualize the survey findings and explore educators’ lived experiences in greater depth, we conducted semi-structured focus groups with a purposive sample of CRNA program faculty and clinical preceptors. The focus group script was developed based on preliminary survey themes and included open-ended questions exploring variability in institutional expectations for POCUS instruction, personal confidence levels in teaching ultrasound techniques, challenges in equipment access and simulation fidelity, reactions to the inclusion of newer modalities such as TEE, and ideas for improving national standardization of POCUS curricula.

Data Collection and Analysis

Thematic analysis of focus group transcripts allowed triangulation of the survey data and identification of nuanced barriers and opportunities not captured through quantitative questions alone. All information collected was anonymous and stored on secure servers. The data was exported to Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and analyzed for emerging trends. Quantitative data was analyzed using Microsoft Excel and SPSS to generate descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages, and measures of central tendency. Open-ended responses were analyzed thematically using content analysis to identify common patterns and nuanced perspectives on educational challenges and innovations. Cross-tabulation was performed to explore associations between educator experience and reported instructional practices. Descriptive statistics were computed using Microsoft Excel to summarize response frequencies and trends.

Qualitative thematic analysis identified 3 primary themes from educator responses: (1) limited educator comfort and proficiency in teaching specific POCUS applications, (2) anatomical variations posing teaching challenges, and (3) constraints of limited instructional and clinical time. These themes underscore significant obstacles to effective POCUS curriculum implementation, highlighting the critical need for structured educator training and clearly defined instructional frameworks.

Results

Survey responses were collected exclusively at the ADCE meeting held in February 2023. A total of 116 conference attendees participated in the survey, representing 32 U.S. states. Among these, 28 states currently host CRNA training programs. Florida and Texas were overrepresented, likely due to the conference’s geographic location. Most respondents were from non-opt-out states (80%) and non-independent practice states (63%). The majority had extensive clinical experience, with 51% reporting more than 15 years in practice. Additional experience breakdowns included 10–15 years (23%), 5–10 years (18%), and 1–4 years (8%).

Regarding teaching experience, 26% of respondents reported 3–5 years of teaching, followed by 24% with 10–15 years, 19% with over 15 years, 16% with 6–10 years, and 15% with 1–2 years.

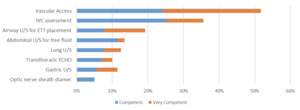

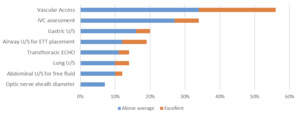

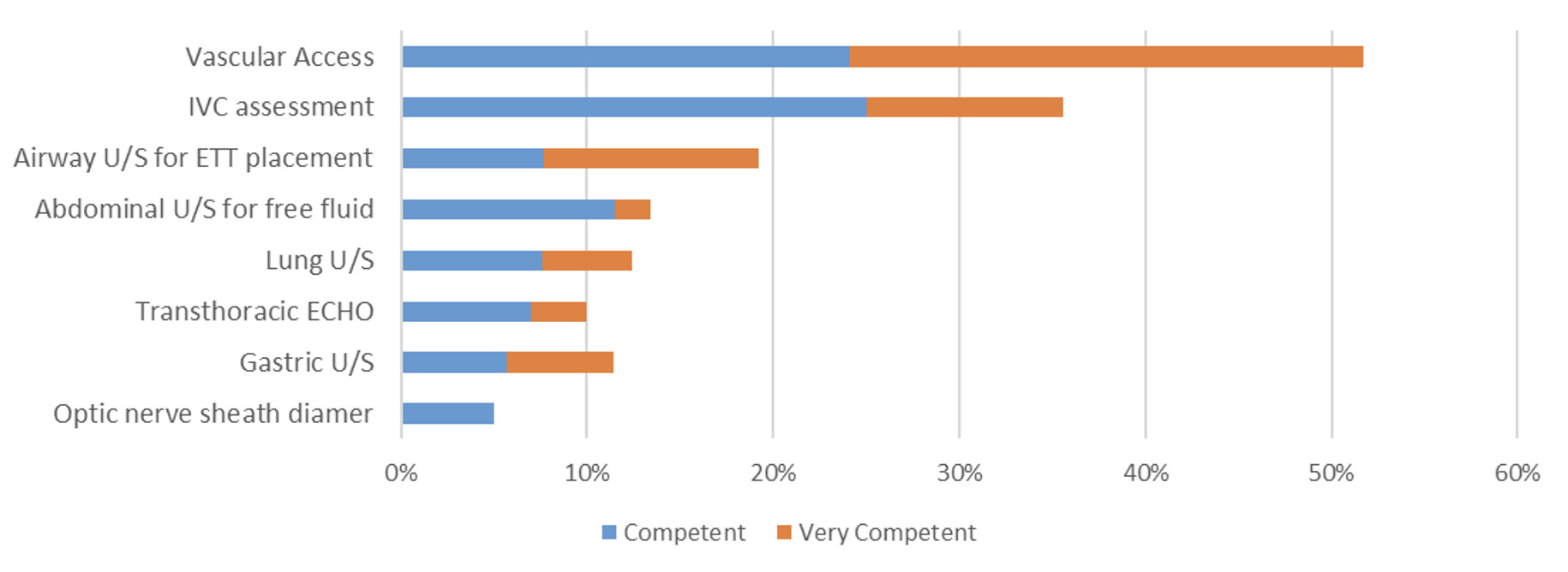

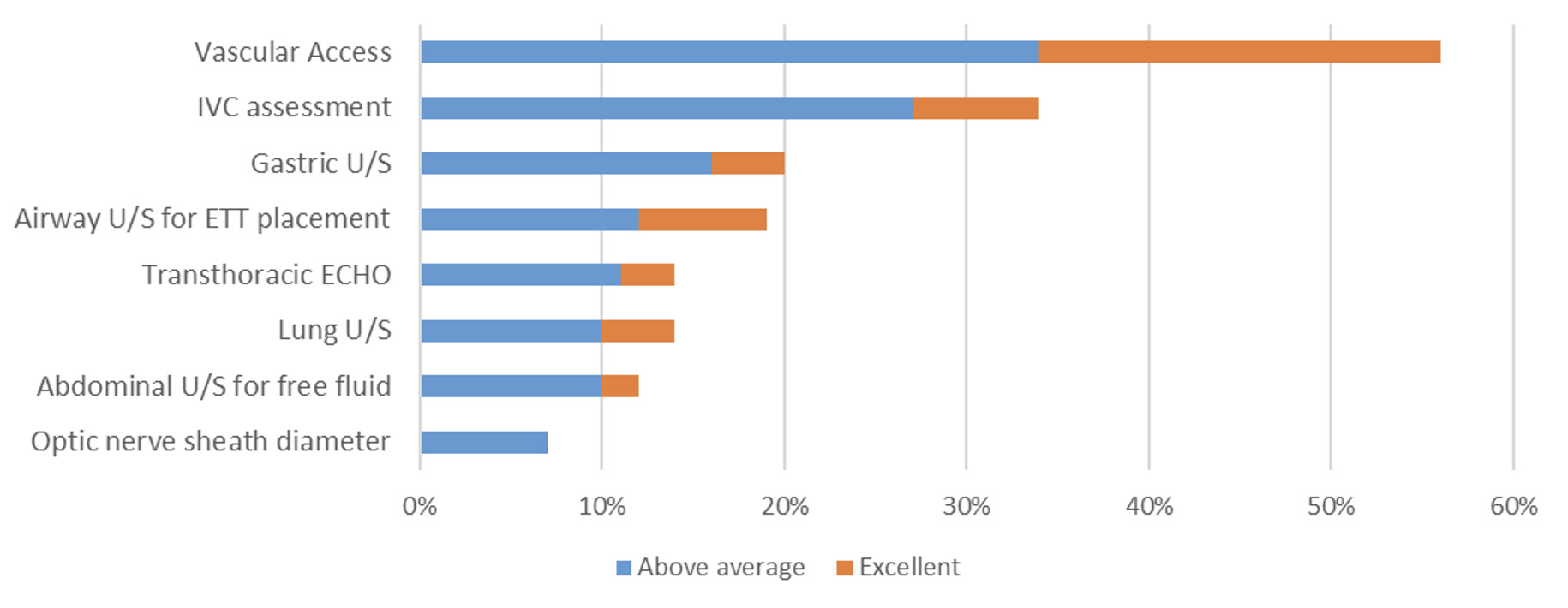

Self-Perceived Competency and Comfort Teaching POCUS

Participants assessed their own competency across various POCUS modalities using a 4-point Likert scale. Proficiency was highest in vascular access, with 52% reporting themselves as competent (24%) or very competent (28%) (Figure 1). IVC assessment followed, with 36% rating themselves as competent (25%) or very competent (11%). For all other studies, airway, abdominal, lung, GUS, TTE, and ONSD competency levels were markedly lower, ranging from 5% to 19%. Self-perceived comfort in teaching these techniques paralleled reported competency levels. Respondents expressed the most confidence teaching vascular access and IVC assessments, while comfort levels teaching TTE, lung, airway, and ONSD were low (Figure 2).

Preferred Learning Modalities

When asked about preferred educational formats for skill acquisition, 50%–62% of respondents favored intensive 2-day workshops featuring live scanning across most modalities. TTE was the exception, with 47% preferring longer 8–10 day educational series incorporating live scanning and simulation.

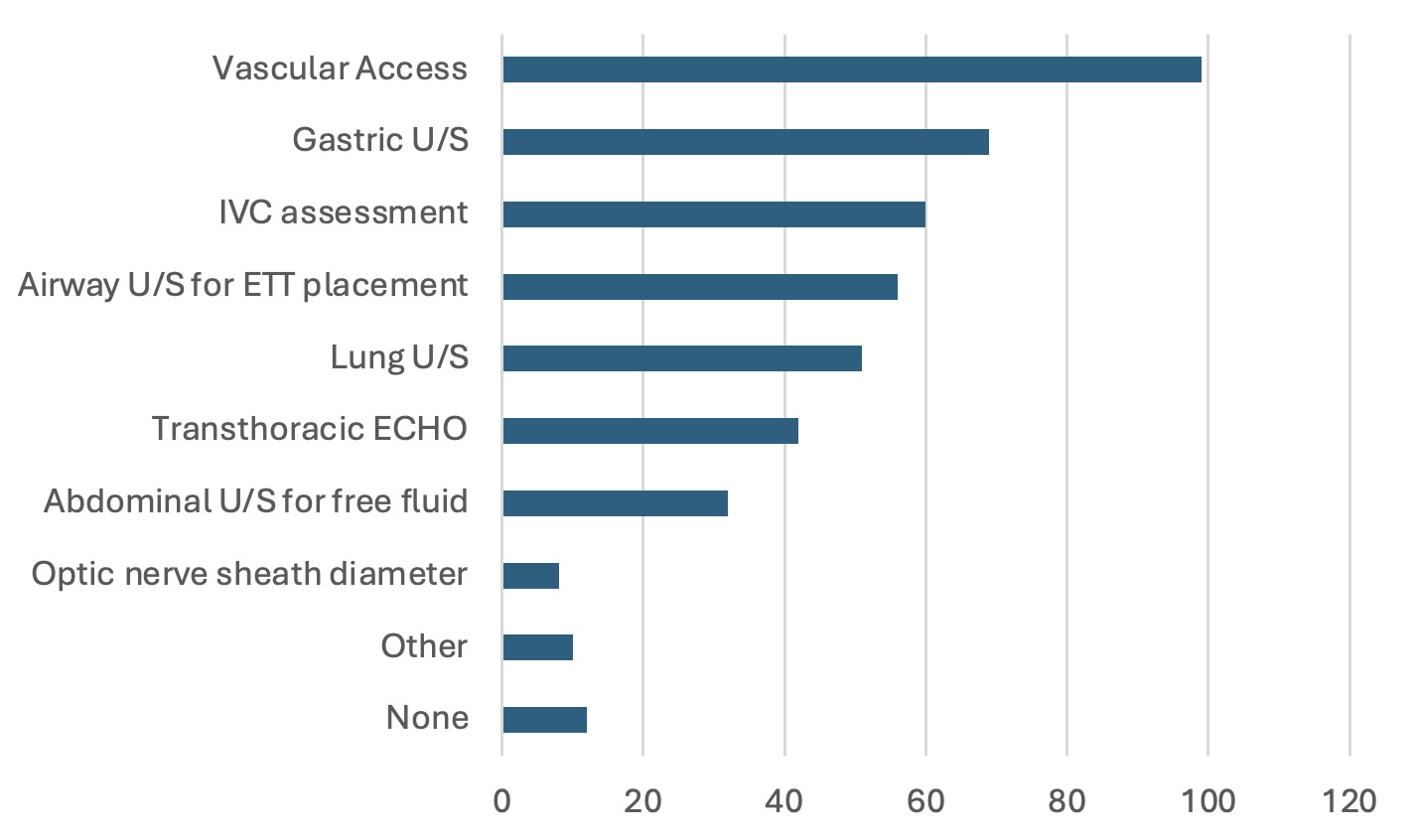

Current POCUS Teaching Practices

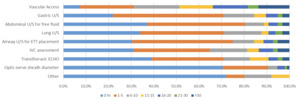

Current teaching practices varied significantly across institutions (Figure 3).

Vascular access was taught in 85% of programs, followed by GUS (59%) and IVC assessment (52%). Other modalities, including airway (48%), lung (44%), TTE (36%), abdominal (28%), and ONSD (9%), were far less commonly included in curricula. Notably, 10% of respondents indicated POCUS was not part of their formal curriculum, and only 5% reported having a dedicated ultrasound rotation. The most frequently used teaching methods included simulation sessions (78%) and lectures (72%). Less commonly used modalities were bedside instruction (53%), structured hands-on scanning (50%), and expert demonstrations (46%). Other methods such as online modules (40%), image review (37%), and elective or extracurricular rotations were rarely employed.

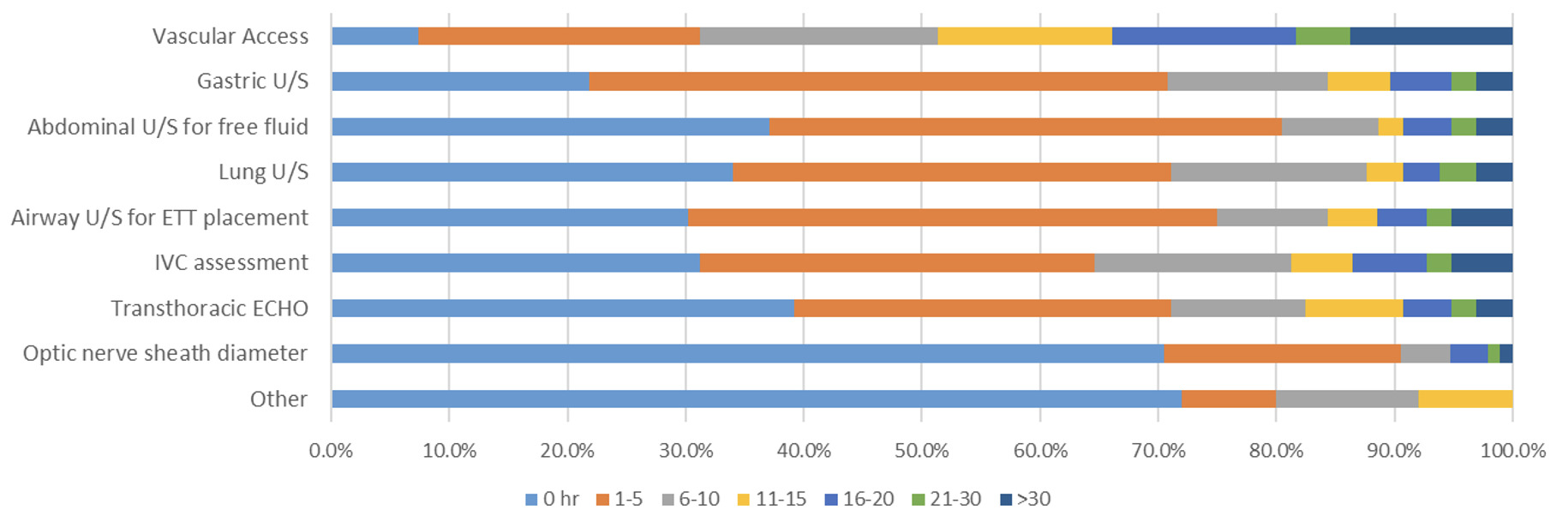

Training Hours and Clinical Exposure

Formal training hours were limited. For vascular access, 59% reported 1–5 hours of instruction, while 15% reported less than 1 hour or no training. For GUS, IVC, TTE, airway, and lung assessments, 36–48% of respondents indicated 1–5 hours of formal training, while 41–63% reported less than 1 hour or none. ONSD training was especially scarce, with 66% of programs providing no instruction. The number of scans performed by residents reflected these instructional gaps (Figure 4). Only 7% of respondents reported that their residents performed no scans for vascular access. In contrast, high percentages of faculty reported residents performed zero scans in GUS (22%), abdominal (37%), lung (34%), airway (30%), IVC (31%), TTE (39%), and ONSD (71%).

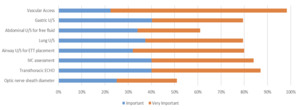

Perceived Importance and Evaluation

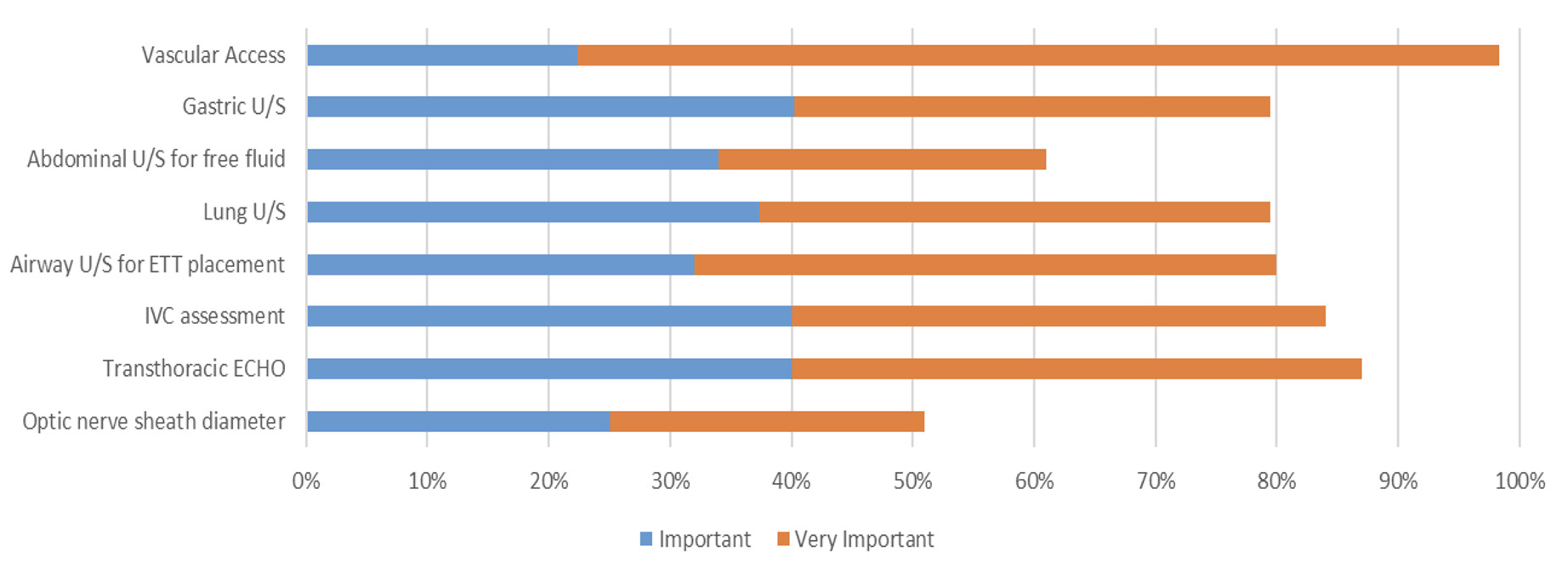

Educators overwhelmingly perceived POCUS as necessary for CRNA training. At least 80% rated GUS, lung, airway, and IVC assessments as important or very important (Figure 5).

Vascular access and TTE were considered important or very important by 98% and 87% of respondents, respectively. ONSD was viewed as less critical, with 51% rating it as less important. During focus groups, the additional theme found regarding TEE was reported as not essential, but as a skill that CRNA providers would like to receive training and education on.

When asked about the need for improvement, 93% cited TTE training, followed by airway (87%), lung (85%), GUS (84%), IVC (84%), abdominal (82%), vascular access (79%), and ONSD (78%). Most respondents (96%) agreed that POCUS skills should be formally evaluated, yet 42% reported that no such assessments are currently in place at their programs.

Barriers to Implementation

Respondents identified several barriers to POCUS education. The most significant included the lack of a formalized POCUS rotation (82%), insufficient qualified instructors (79%), and absence of a standardized curriculum (70%). Additional challenges included inadequate clinical time (69%), limited equipment availability at clinical sites (62%) and within programs (61%), and lack of instructional resources (55%). Only 29% of respondents considered a lack of resident interest a barrier.

Discussion

Our study reveals a significant mismatch between the perceived importance of POCUS competencies and their implementation within CRNA curricula. Educators consistently highlighted the necessity for standardized training and formal evaluation methods, aligning closely with AANA and COA educational standards. However, substantial gaps persist due to limited structured curricula, inconsistent teaching methods, and inadequate assessment rubrics. These findings strongly advocate for immediate development and integration of structured, competency-based curricula supported by formal rubrics and clear competency assessments to ensure consistent and robust training standards. Consistent with findings in anesthesiology residency programs, this study shows that educators feel most proficient in teaching vascular access, a modality long established in anesthesia practice.25–27 However, competency sharply declines across more advanced or emerging POCUS applications such as TTE, ONSD, and GUS.14,15 These results mirror prior research that educators are generally more comfortable teaching familiar techniques and often lack training and confidence in newer or less frequently used ultrasound applications.18,23

This disconnect poses a significant challenge for developing comprehensive ultrasound curricula. Despite strong educator support for including POCUS in training, limited faculty expertise remains a significant barrier. As reported in our study and supported by previous literature, a lack of qualified instructors is one of the most frequently cited obstacles to curriculum development and effective delivery.15

Inadequate Structure and Standardization

A central concern is the absence of formalized training structures across nurse anesthesia programs. In our findings, only 5% of programs report a dedicated ultrasound rotation, and many offer less than 5 hours of total instruction for most modalities. This underscores the inconsistency of training across programs. These patterns align with prior surveys in both medical and advanced practice training, which have shown variable integration of POCUS instruction and little standardization across institutions.18,20,28

The lack of standardization undermines skill acquisition and affects learner confidence and patient safety. In both NP and PA literature, structured POCUS programs are associated with better learner outcomes, including more frequent use of ultrasound during clinical rotations and improved diagnostic.20 Our findings support these conclusions by showing that limited training hours and lack of structured exposure result in fewer student-performed scans and low faculty comfort teaching most modalities.18

Mismatch Between Perceived Importance, Training and Practice

Educators overwhelmingly agreed on the importance of POCUS training, with more than 80% rating nearly all modalities as “important” or “very important” for NARs. Yet, this conviction has not translated into practice. Most programs lack formal assessments, and exposure to modalities such as TTE, lung, airway, and ONSD ultrasound remains limited. This mirrors similar gaps in internal medicine and pediatric residencies, where enthusiasm for POCUS is not always matched by implementation.27

Furthermore, our results show that while faculty value training improvement, particularly for advanced modalities like TTE and TEE, meaningful program changes are hindered by infrastructural limitations. Respondents cited a lack of formal rotations (82%), qualified faculty (79%), and standardized curricula (70%) as leading barriers, reinforcing the need for institutional support, equipment investment, and curriculum reform.

As highlighted in recent literature, faculty development programs significantly improve confidence, image acquisition skills, and teaching engagement among ultrasound educators.29 Our findings corroborate this, suggesting that empowering educators through structured, longitudinal faculty training, rather than one-time workshops, may be critical for improving both educator competence and downstream student outcomes.

Limitations

It is important to note that 51% of respondents had been practicing CRNAs for 15 or more years, followed by 23% at 10-15 years. Curriculum has changed over the years. We did not complete a subgroup analysis of years as a CRNA and comfort, but the fact remains there are steps for educators to take if their perceived comfort is low for teaching POCUS, regardless of years teaching or years of experience.

Recommendations and Implications

Recommendations for faculty include POCUS training with continued practice. Courses that request a portfolio have been shown to have a greater impact on learners.23,24 Faculty who completed an image portfolio scored higher on knowledge assessments and reported greater confidence in image acquisition and interpretation. These faculty members were more actively engaged in teaching POCUS compared to counterparts who did not complete the portfolio. The study concludes that POCUS education programs should be designed to foster continuous scanning practice and image portfolio completion to enhance long-term proficiency among faculty.23,24 While this study did not explicitly query educators about portfolio use, existing literature strongly supports the implementation of portfolios to enhance teaching effectiveness and learner competency in POCUS.

Engaging teaching techniques during instruction of POCUS should be incorporated, such as into simulation scenarios, case studies, portfolio presentation, and teach-back methods. To close the gap between expectations and implementation, CRNA programs should at minimum consider the following:

For faculty:

-

Invest in faculty development pathways.

-

Create scanning portfolios to review with content experts.

-

Leverage simulation and online platforms to scale instruction and overcome time and resource constraints. (Although specific questions about online learning were not included in the survey, online platforms have demonstrated effectiveness in related educational literature, suggesting potential applicability to POCUS education.)

For students:

-

Initiate competency standards and assessment tools aligned with other anesthesia specialties.

-

Dedicate POCUS rotations for students with hands-on scanning requirements.

-

Implement student portfolio requirements to enhance individual accountability and systematically track competency development in POCUS skills.

Leadership from professional organizations such as the AANA or collaboration with recognized third-party educational leaders could effectively drive standardized curriculum development and faculty training initiatives, enhancing uniformity and effectiveness of POCUS education nationwide. Receiving proper training will help ensure that future CRNAs are equipped with the skills needed to safely and effectively apply ultrasound in clinical practice.

Conclusion

Critical gaps in POCUS education for CRNA programs necessitate immediate implementation of structured curricula, dedicated rotations, and comprehensive educator training programs. Establishing standardized protocols will significantly enhance clinical competencies among future CRNAs. Future research should explore the efficacy of various training models, including simulation-based education and interdisciplinary collaborations, to determine best practices for POCUS skill acquisition. National-level benchmarking and consensus-building efforts should be prioritized to guide competency expectations and programmatic accreditation standards.