Introduction

Peripheral nerve blocks (PNB) are vital to any multimodal pain management approach and can effectively reduce postoperative pain with minimal side effects.1 Pain significantly affects the patient, and using regional techniques for preemptive anesthesia can improve heart and lung function, decrease blood loss, lower anesthesia-related side effects, shorten hospital stays, and reduce postoperative pain, nausea, and vomiting.2–4 This approach also enhances patient satisfaction.2,3 Current evidence shows fewer adverse events and increased safety when using ultrasound-guided PNBs.4,5

Certified Registered Nurse Anesthesiologists (CRNA) are trained and credentialed to perform Ultrasound Guided Regional Anesthesia (UGRA). While providers are expected to offer these services at their workplaces, infrequent use of PNB skills can lead to reduced confidence and hesitance in performing them clinically. The limited practice of performing PNBs emphasizes the need for a Program Development Initiative focused on providing UGRA training for CRNAs. This training aims to improve their knowledge, technical skills, and confidence in performing PNBs. Ultimately, this initiative can help address healthcare gaps by increasing the number of providers capable of delivering advanced pain management, thereby enhancing patient safety and satisfaction. Consequently, this pilot program seeks to increase the number of PNBs performed by CRNAs in clinical settings. Its secondary goal is to expand CRNAs’ knowledge and skills related to PNBs.

The simulation-based training program aimed to enhance CRNA knowledge, technical skills, and confidence in performing PNBs. It began with a pre-survey to assess their baseline ability and self-reported confidence in applying PNBs in clinical practice. CRNAs reviewed a PowerPoint presentation on the basic anatomy and clinical indications of the 4 PNBs planned to be used in the simulation. Before the hands-on simulation, a structured pre-briefing session was held, where the 4 PNBs were presented and discussed in detail through a live lecture. CRNAs were subsequently divided into 4 small groups of 2-3 participants each for individualized instruction at each station. The 4 PNB stations were: interscalene, supraclavicular, adductor canal, and transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block. Each group participated in hands-on training with ultrasound-guided techniques, utilizing standardized patients and task trainers, under the direct supervision of subject matter experts. A debriefing session concluded the simulation after station rotations. CRNAs were informed that a follow-up survey would be conducted to evaluate changes in their clinical application of PNBs, including their ability to perform the blocks and their confidence levels after the training. The primary outcome measure of this initiative included comparing the number of PNBs performed by the CRNAs before and after a simulation training program. The secondary outcome measure assessed each CRNA’s perceptions of their PNB skills and knowledge.

The literature review included a search of PubMed, CINAHL, OVID, EMBASE, Cochrane, and PsycINFO. The keywords “regional anesthesia and simulation-based training,” “simulation-based training,” “peripheral nerve blocks and the use of a simulation-based training program,” “effects of a simulation-based training day and clinical performance,” “simulation-based training and self-confidence,” “simulation-based training versus conventional learning,” and “clinical performance with the use of a simulation-based training day” were used during the search. Thirty-one references were included, with 18 published within the last 5 years and 13 published more than 5 years ago.

Methods

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined that the PNB simulation training program was not classified as research and granted it an exempt status. A convenience sample of CRNAs working at a Level I trauma center was recruited through flyers in the breakroom, postings on a CRNA group messaging app, and through email. To assess initial interest, CRNAs were invited to complete a survey about their intention to participate in a PNB simulation workshop. The simulation training was conducted at a simulation center, giving CRNAs hands-on experience as they practiced PNBs.

After receiving IRB approval, information was shared with participating CRNA participants to explain the overall aim, scope, and purpose of the simulation-based training program. Administrators and CRNA participants were blinded to the CRNAs’ identities, and the results were destroyed after the program was completed. The CRNAs were asked to complete an anonymous registration and survey through Qualtrics. The Qualtrics registration was stored separately from the survey response data on a password-protected computer, and both were deleted after the simulation training program ended. Additionally, only the simulation directors had access to the registration roster, while statisticians could access the survey response data, which contained no personally identifiable information. This secure, cloud-based platform included demographic details, baseline PNB knowledge, informed consent, and acknowledgment of the voluntary nature of the training. The demographic questions were designed to be broad to prevent identification of individual CRNA participants based on their responses. The 30 questions on Qualtrics, created by CRNA PNB subject matter experts, evaluated CRNA participant general knowledge of PNBs.

CRNAs were asked to complete the 16-item Evidence-Based Practice Belief (EBP-B) scale to administer PNBs within their practice settings before the training session. This instrument included statements rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. Each response was assigned a number (1 to 5), and scores were summed after completion, resulting in a total score between 16 and 80. Researchers Kerwien-Jacquier et al6 and Melnyk et al7 have conducted studies evaluating the reliability and validity of the EBP-B instrument and found that it demonstrates strong psychometric properties. A higher score on the EBP-B indicated a stronger belief in the frequency of PNBs performed and greater confidence in conducting them within current clinical practice. Additionally, this scale has demonstrated sensitivity to interventions and internal consistency-reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha above 0.85.8

Six weeks before the simulation training program, the CRNA participants viewed a PowerPoint presentation that provided a baseline knowledge review of the 4 PNBs planned to be used in the simulation. The CRNAs were oriented to the simulation environment and had the opportunity to ask questions about the 4 PNB stations. Upon arrival at the simulation center, the CRNAs received an orientation to the facility and had the opportunity to ask questions about the PNB training stations. The simulation stations were separated by moveable privacy barriers, placed 6 to 8 feet apart. Each station was equipped with a stretcher, ultrasound machines, and PNB task trainers for each nerve block, which included equipment kits and needles. Paid actors played standardized patients and were provided comfort measures such as warm blankets, pillows, a space for belongings, and took 15-minute breaks between station rotations. These simulated patients allowed the CRNAs to perform ultrasounds and physical assessments to identify landmarks, while the needles were used only with the PNB task trainers. The 7 expert CRNAs leading the training had diverse and advanced qualifications, including a university dean who actively practiced clinical PNBs, 3 CRNAs proficient in placement of PNBs, 4 had Certified Healthcare Simulation Educator credentials, and 1 was the Director of an Advanced Pain Management Fellowship within a nurse anesthesia program.

Participating CRNAs engaged in 1-hour sessions at each of the stations, during which they reviewed the targeted PNB, practiced ultrasound-guided techniques on standardized patients, and performed block procedures on task trainers specifically designed for the corresponding PNB. Each station concluded with a structured debriefing to reinforce learning and facilitate reflective practice. During these debriefings, the CRNAs were guided to reflect on their experiences and identify strengths and areas needing improvement. This approach, known as debriefing for meaningful learning, focuses on enhancing simulations with additional knowledge and best practice techniques to promote critical thinking and has a more significant impact on learning outcomes than other debriefing methods.9,10 During the debriefings CRNAs identified a lack of support in the Level 1 trauma center for PNB administration by CRNAs, but they stated that the simulation workshop provided a good review and hands-on practice of the 4 PNBs discussed during the sessions. Follow-up information from the debriefing exercise included 1 technical question regarding hands-on techniques.

Following completion of the PNB simulation workshop, CRNA participants completed a 30-item assessment developed by administrative CRNAs in collaboration with content experts to satisfy the American Association of Nurse Anesthesiology (AANA) criteria for Class A Continuing Education Units (CEUs). This data helped evaluate any changes in the confidence and knowledge of the CRNAs performing PNBs in their practice. Outcomes were assessed by comparing pre- and post-simulation survey results. The CRNAs received a certificate of completion after finishing the simulation-style training program. Participating CRNAs earned 6 AANA Class A CEUs.11 After the training, all paper records were securely shredded, and electronic files deleted.

Statistical Analysis

Pre-implementation and post-implementation data, including the number of PNB performed, EBP-B scores, and assessment test scores were compared. The data were entered into and analyzed with Microsoft Excel, imported into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences 26.0, and checked for missing values and accuracy. Count data (e.g., the number of blocks performed per CRNA before and after implementation) were described using means.

The pre- and post-implementation surveys were given to the same group of CRNAs to assess changes in knowledge, confidence, and perceptions related to PNB procedures. The data are considered paired because the same individuals were evaluated at 2 different times. Paired data occurs when measurements are repeated on the same subjects, creating a natural link between observations. This method allows for analyzing within-subject changes over time, increasing the statistical power to identify significant differences caused by the intervention.12

The EBP-B scores and assessment test scores were described using an interquartile range. Changes in the number of PNBs performed after implementation, EBP-B scores, and assessment test scores were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U test because survey responses were collected anonymously. The impact of the intervention on the number of blocks performed per CRNA, EBP-B scores, and assessment test scores was assessed using the Mann-Whitney U test at an alpha level of < 0.05 for all tests. This statistical analysis ensured the reliability and validity of the results, increasing confidence in the outcomes of the simulation training program.

Results

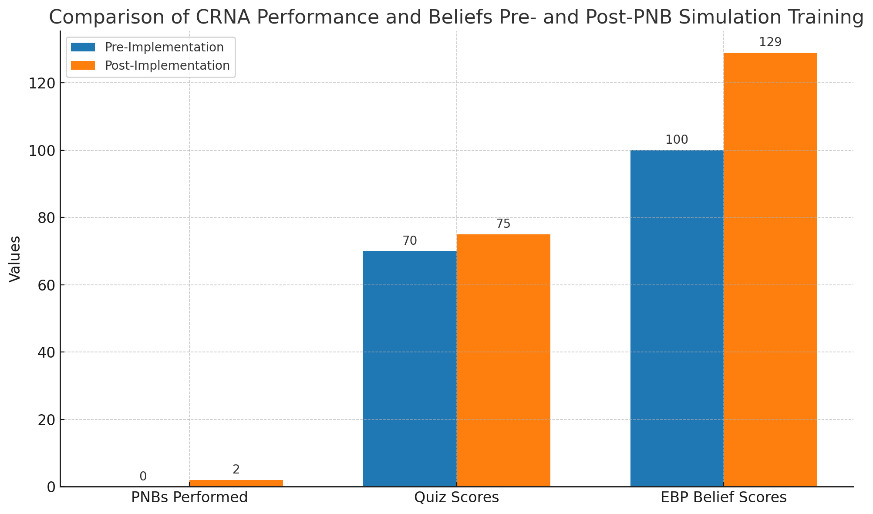

Following the formal implementation of the simulation-based PNB training for CRNAs, pre-implementation data were collected over 1 week, while post-implementation data collection was conducted over 6 weeks to evaluate the training’s impact. Data was gathered on a total of 9 CRNAs, pre- and post-implementation. Pre- and post-implementation data, including the number of PNB procedures performed, EBP-B scores, and assessment test scores, were collected via email and then compared to assess the effectiveness of the simulation training program. Before the simulation program, the mean PNB performed by the CRNAs was zero compared to the mean of 2 PNB performed after implementation. The number of PNBs performed by CRNAs increased by 33% after implementation (p = 0.25). See Table 1. After implementation of this initiative, assessment test scores increased (median difference +5, p = .001), and EBP-B scores also increased (median difference +29, p = .001). See Figure 1.

Discussion

The primary goal of this program was to determine if the number of PNBs performed increased after completion of an education-based simulation initiative. The ability to perform a PNB supports CRNA full scope of practice to the extent of their licensure and training. A literature review showed that multiple studies reported significant improvements in knowledge, clinical skills, and confidence through simulation-based learning.13–27 A systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with meta-analysis found increased performance and knowledge scores after simulation training (95% CI = 0.48 to 1.31; p < .001) compared to other teaching methods.15,16 In another RCT, Weber et al28 showed that simulation-based training is more effective for improving psychomotor skills and knowledge (p < .001) than electronic learning or other traditional didactic approaches to teaching nerve anatomy and psychomotor skills. Although the rise in PNBs performed after simulation training was promising, total numbers remained low. This modest growth may stem from systemic barriers in clinical settings, such as physician gatekeeping, which can limit access to procedural opportunities.

The secondary outcome evaluated CRNAs’ perceptions of incorporating UGRA into their daily routine after completing the PNB simulation training. The simulation training results revealed a positive impact on CRNAs’ confidence and perceived ability to perform UGRA during PNB procedures. This aligns with current evidence that simulation-based courses on UGRA effectively improve CRNAs’ knowledge, skills, and confidence while decreasing pain scores during and after surgery, ultimately leading to better patient outcomes.13,17,18,29 Increased scores were observed in both knowledge and beliefs regarding evidence-based practice (EBP). Post-training assessment test scores increased (median difference = +5, p = .001), indicating enhanced understanding of PNB techniques. Additionally, EBP-B scores were significantly higher following the intervention (median difference = +29, p = .001), reflecting a stronger belief in the importance and application of EBP in clinical practice. These results support the effectiveness of simulation-based education in improving both cognitive skills and attitudinal perspectives among CRNAs.

Limitations

One limitation of this simulation-based training program was a small number of CRNAs (N = 9) from 1 hospital setting. Another limitation was that each CRNA’s experience was unique, meaning 1 CRNA may have needed a more in-depth explanation of a particular PNB than another. While the CRNAs could use the ultrasound on an actual individual to identify pertinent anatomy for each block, they could not administer PNBs to these volunteers, limiting the extent of their experience. Another limitation of this study is the use of a convenience sample from a single hospital where CRNAs face institutional restrictions on performing PNBs. Although this site was chosen for accessibility, it might not represent the wider CRNA population, especially in areas where CRNAs can practice to the full extent of their training and licensure and independently perform PNBs.30 Another limitation is the use of manikins to help CRNAs identify anatomy and guide the needle during PNB placement with ultrasound. These manikins have padding that indicates where the blocks should be placed. In clinical practice, each patient has unique anatomical variabilities, which are hard to replicate with simulation manikins. The most important limitation of this initiative was the reluctance of physician anesthesiologists at the institution to collaborate with CRNAs to perform PNBs at their institution, which limited opportunities for them to apply learned skills to practice.

As noted in the introduction, inconsistent use of PNB skills in clinical practice, despite institutional expectations to provide these services, can reduce providers’ confidence and lead to hesitancy in performing them. This gap in routine practice highlighted the need for a program development initiative focused on UGRA training to improve CRNAs’ knowledge, technical skills, and confidence in administering PNBs. While CRNAs acknowledged a lack of institutional support for performing PNBs within the Level 1 trauma center setting, they reported that the simulation workshop was a valuable refresher for skill and knowledge and provided meaningful hands-on experience with the 4 targeted PNBs introduced during the training.

Implications to Practice

Today, PNBs are an integral part of the perianesthesia process, as they are used for various surgical pain control procedures, including breast, thoracic, pediatric, abdominal, and spine procedures.31 Types of PNBs include upper extremity blocks like axillary, shoulder, elbow, hand, and finger blocks or lower extremity blocks like sciatic, femoral, popliteal, knee, ankle, or toe blocks. Analgesic techniques must keep pace with the rapid advancement of surgical specialties. The increased number of minimally invasive techniques has increased the number of outpatient procedures.31

Chang et al16 reported that PNBs are well tolerated and provide superior regional analgesia compared to oral pain medication or general anesthesia. In recent years, PNBs have become an adjunct to anesthesia care worldwide, especially since the introduction of ultrasound technology, which offers technical simplicity with an increased safety margin.31 Using ultrasound guidance techniques has increased the successful placement of PNBs, decreased the need for analgesics during block placement, decreased postoperative rescue analgesia, and decreased vascular injection of local anesthetics. Evidence indicates that ultrasound-guided PNBs are more effective and faster (p < .0001), with a quicker onset of sensory (p = .001) and motor blockade (p < .0001) blockade compared to nerve stimulator (landmark-based) techniques. Additionally, UGRA is associated with fewer complications, further supporting ultrasound as the superior method for performing PNBs.29,32 Ultrasound guidance provides direct visualization of needle placement and the target nerve, contributing to the increased safety margin of block placement.33

Utilizing PNBs as part of a multi-modal approach to postoperative pain has contributed to solving the problem of the perioperative opioid crisis, as chronic pain management or opioid-tolerant patients do not have the tolerance to local anesthetics, which has allowed them to become an essential tool for pain control with these patients. Peripheral nerve blocks help facilitate surgical protocols like enhanced recovery after surgery that employ opioid-sparing or non-opioid techniques.31 Opioids have traditionally been used for postoperative pain control but include risks like addiction, respiratory depression, nausea, vomiting, cognitive impairment, and somnolence. Studies indicate that the increased use of PNBs has led to decreased opioid consumption, pain scores, and adverse effects of opioids when compared to patients who receive systemic analgesia or general anesthesia alone.34

There are no set protocols for using PNBs. However, their implementation is generally justified when conservative pain control measures have not proven successful or to avoid complications of oral pain medications or general anesthesia.16 They can also be used as an adjunct to multimodal analgesia when the goal is to target various parts of the pain pathway, thus decreasing pain and delivering fewer side effects during recovery.

Regional analgesia provided by PNBs is beneficial when general anesthesia may not be an option because of coexisting comorbidities or as an option when minimal sedation is preferred.34 They provide pain control during and after surgery, can be used as an alternative or supplement to general anesthesia, and can improve patient satisfaction while providing the added environmental benefits of decreased usage of anesthesia gases and other medications.33

The benefits often outweigh the risks when using PNBs for pain control; however, risks must be considered during clinical practice. Risks include local anesthetic systemic toxicity syndrome, nerve damage, bleeding, and infection. Other limitations or contraindications are patients’ inability to cooperate with or outright refusal to consent to the PNB procedure. It is also advised to postpone or reconsider nerve injection if there is an active infection at the injection site, if there are other nerve deficits present, if there is coagulopathy, or if the patient takes blood thinners.

Ultrasound technology has improved the efficacy and safety of PNBs by increasing successful placement and decreasing complications.34 PNBs have been a significant advantage in surgical pain management, providing patient comfort throughout the perianesthesia process.

Next Steps

This simulation workshop was conducted on a small scale at one Level 1 trauma center to evaluate the quality and effectiveness of the implementation process. The information collected during this experience provided insights into future planning and modifications for a broader program that could benefit the perianesthesia team across multiple facilities. This program’s recruitment rate was low, and it is a key part of a pilot that assesses its feasibility for future projects. The program included perianesthesia nurses and CRNAs; therefore, the authors recommend using this program’s design for annual quality improvement simulations or protocol training for the entire perianesthesia team to boost participation.

Future efforts should aim to expand the feasibility and scalability of the PNB simulation-based training. Given its success in enhancing CRNA knowledge, confidence, and evidence-based practice beliefs, incorporating it into institutional onboarding for new anesthesia providers could improve early clinical competency. Additionally, including the program in annual competency assessments may promote skill retention and maintain proficiency in UGRA.

There is also potential for interprofessional simulation initiatives, where CRNAs train alongside other anesthesia team members, to promote collaboration and streamline workflow during PNB procedures. Systematic implementation across institutions could further standardize UGRA training and support CRNAs in practicing to the full extent of their licensure. Other suggestions include offering the program multiple times over a longer period to involve swing or night shift staff. Including students, whether nursing students, nurse anesthesia students, or physician residents, if available, could also help increase workshop participation.

Conclusion

The findings of this PNB simulation-based training program highlight the value of simulation-based education in strengthening the knowledge, beliefs, and confidence of CRNAs in performing peripheral nerve blocks. While the increase in the number of PNBs performed post-intervention was not statistically significant, the statistically significant improvements in knowledge and EBP-B scores suggest meaningful educational gains. These results emphasize the importance of structured, evidence-based training opportunities, particularly for CRNAs with limited autonomy or exposure to advanced regional anesthesia techniques in their clinical settings. With refinement and broader implementation, similar workshops have the potential to standardize competency development and support ongoing professional growth among CRNAs across diverse healthcare environments.