Introduction

Despite a growing body of literature addressing incivility in undergraduate nursing education, there remains a notable paucity of qualitative and mixed-methods research examining clinical preceptor incivility within nurse anesthesiology education specifically. This gap is particularly concerning given the high-acuity clinical environment, steep learning curve, and increasing workforce demands faced by nurse anesthesiology residents. Limited empirical evidence exists describing how residents experience preceptor incivility, how these interactions influence professional identity formation, and what systemic factors may perpetuate such behaviors, underscoring the need for focused investigation in this population.

In addition to gaps in the literature, workforce-level pressures further underscore the need to examine clinical learning environments in nurse anesthesiology. The United States continues to experience a persistent shortage of Certified Registered Nurse Anesthesiologists (CRNA), alongside high levels of occupational stress and burnout associated with the cognitive, emotional, and technical demands of anesthesia practice. Burnout and compassion fatigue have emerged as critical concerns among CRNAs and nurse anesthesiology residents in today’s high-pressure healthcare environments. The cumulative effects of long hours, emotional labor, and high-stakes clinical responsibility place professionals at risk for exhaustion, disengagement, and diminished resilience. Nurse anesthesiology residents are educated within this context of workforce strain and are expected to rapidly develop advanced clinical judgment in high-acuity environments.1

In the high-stakes, high-acuity environment of nurse anesthesiology education, the development of professional identity is intimately shaped by the clinical preceptorship experience. Clinical preceptors serve not only as educators but also as role models, evaluators, and gatekeepers of patient safety. However, when preceptorship is marred by incivility, ranging from dismissiveness and ridicule to exclusion and unfair evaluation, it can undermine the educational process and compromise the well-being and confidence of nurse anesthesiology residents.

Within healthcare education, incivility is conceptualized as a pattern of intentional negative behaviors that are perceived by recipients as harmful, emotionally distressing, and disruptive to learning and professional functioning.2 While incivility has been explored extensively in undergraduate nursing programs, little is known about its impact within graduate-level nurse anesthesiology training, where the stress is heightened and expectations for independence are rigorous. Clinical preceptors, whether CRNAs or anesthesiologists, hold substantial influence over a resident’s learning experience, and incivility in these relationships may cause long-lasting effects on professional identity, performance, and future practice.

Cultivating and maintaining a culture of civility between nurse anesthesiology residents and their clinical preceptors leads to building meaningful relationships, creating healthy educational environments, and fostering a sense of organizational belonging. Incivility in nursing education fosters negative teaching and learning environments within the classroom and may discourage residents from continuing in the profession. Such behaviors, including bullying, cause professional harm to nursing students and undermine their growth. Academic incivility also diminishes the well-being of its recipients and stands in direct opposition to the values of compassion and respect that define the nursing profession.3

Ultimately, this development of a strong cultural foundation results in more favorable resident experiences and increased patient safety.4 Promoting mutual respect, dignity, and psychological safety within clinical education extends beyond mentorship and resident well-being to influence patient safety and outcomes. In anesthesia practice, where vigilance, communication, and rapid decision-making are paramount, psychologically safe environments encourage learners to ask questions, voice concerns, and report potential errors without fear of ridicule or retaliation. Conversely, incivility may suppress communication, undermine team functioning, and increase the risk of adverse events, thereby affecting not only individual learners but also the patients and populations they serve.

Background/Significance

A growing body of literature describes the adverse effects of incivility in nursing education. Academic incivility behaviors range from disruptive behaviors and annoyances to threatening behaviors such as intimidation, violence, and attacks.5 Although these dynamics are well documented in undergraduate nursing education, the unique context of nurse anesthesiology education remains largely unexplored. Nurse anesthesiology residents enter their programs as licensed registered nurses but are expected to rapidly develop advanced critical thinking and procedural skills in complex perioperative settings. This transition is often accompanied by intense scrutiny, high expectations, and minimal room for error. Preceptor incivility in such a context, especially when it occurs under the stress of the operating room, can be internalized as personal failure, lead to hesitancy in clinical decision-making, and reduce a resident’s ability to advocate for themselves or patients.

Foreman6 conceptualizes incivility in nursing using the framework of an epidemiological triangle, which includes 3 elements: a causative agent, a susceptible host, and an enabling environment. In this analogy, lateral incivility represents the agent, nursing students serve as the susceptible hosts, and the academic and clinical learning settings form the environment where the “disease” of incivility can spread. Recognizing these relationships may empower students to identify and disrupt the cycle of incivility transmission. Importantly, this framework also emphasizes the role of preceptors as influential agents within the learning environment. Through intentional communication, reflective teaching practices, and awareness of the power dynamics inherent in clinical education, preceptors can actively disrupt the conditions that enable incivility and contribute to a culture of mutual respect, psychological safety, and professional accountability. This shared-responsibility approach shifts the focus from individual behavior to collective cultural change.6

Together, the American Association of Nurse Anesthesiology (AANA), the Association of Perioperative Registered Nurses (AORN), and the American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses (ASPAN)7 authored a white paper on workplace incivility. This joint white paper offers nurses and healthcare institutions clear strategies and practical resources to recognize, assess, address, and report instances of incivility. The AANA, AORN, and ASPAN share a common commitment to fostering the health and well-being of everyone working collaboratively in the perioperative environment.7 While the white paper provided valuable guidance on addressing incivility among healthcare professionals, it did not specifically address behaviors directed by preceptors toward residents. This omission highlights an important gap, as the preceptor–resident relationship can significantly influence both the learning environment and the future culture of the profession.

Research has shown that incivility is not merely an interpersonal concern; it also has system-level consequences. Interprofessional incivility in clinical settings has been linked to decreased team communication, medical errors, increased mortality risk, and compromised patient care.8 Within anesthesia practice, where clarity, speed, and teamwork are essential, the presence of incivility may carry particularly significant clinical implications leading to patient safety events. Despite its relevance, incivility directed at nurse anesthesiology residents remains underrepresented in the literature. There is a need to understand how residents experience preceptor incivility, how they respond to it, and what institutional mechanisms might mitigate its effects. Doing so will better inform the preparation of clinical preceptors and support the cultivation of professional, respectful learning environments in nurse anesthesiology education.

Purpose and Research Aims

The purpose of this qualitative study is to examine the experiences of nurse anesthesiology residents who have encountered incivility from clinical preceptors during their training. In accordance with the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research, the study is guided by the following research questions:

-

What types and patterns of incivility do nurse anesthesiology residents experience in clinical training settings?

-

How do nurse anesthesiology residents perceive the emotional, educational, and professional impacts of incivility, including effects on well-being, learning, professional identity formation, and perceptions of the nurse anesthesiology profession?

-

What coping strategies do nurse anesthesiology residents employ in response to experiences of incivility from clinical preceptors?

-

How do residents believe their experiences with incivility can inform faculty and preceptor development initiatives aimed at promoting civility, effective communication, and constructive feedback?

Understanding these experiences is essential to improving the clinical learning environment, strengthening preceptor–resident relationships, and fostering a culture of respect and professionalism within nurse anesthesiology education.

Methodology

Design

This study utilized a descriptive cross-sectional mixed methods design to explore nurse anesthesiology residents’ experiences with clinical preceptor incivility. The mixed-methods approach combined quantitative and qualitative data collection within a single Qualtrics survey to capture both the prevalence of incivility and the deeper, contextualized perceptions of residents. Quantitative data allowed for identification of trends and frequencies of uncivil behaviors, while qualitative data provided rich narrative insight into the lived experiences, emotional impact, and coping mechanisms of participants.

Survey Development

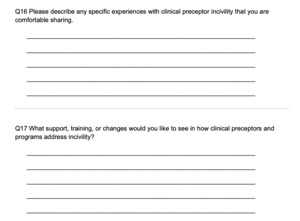

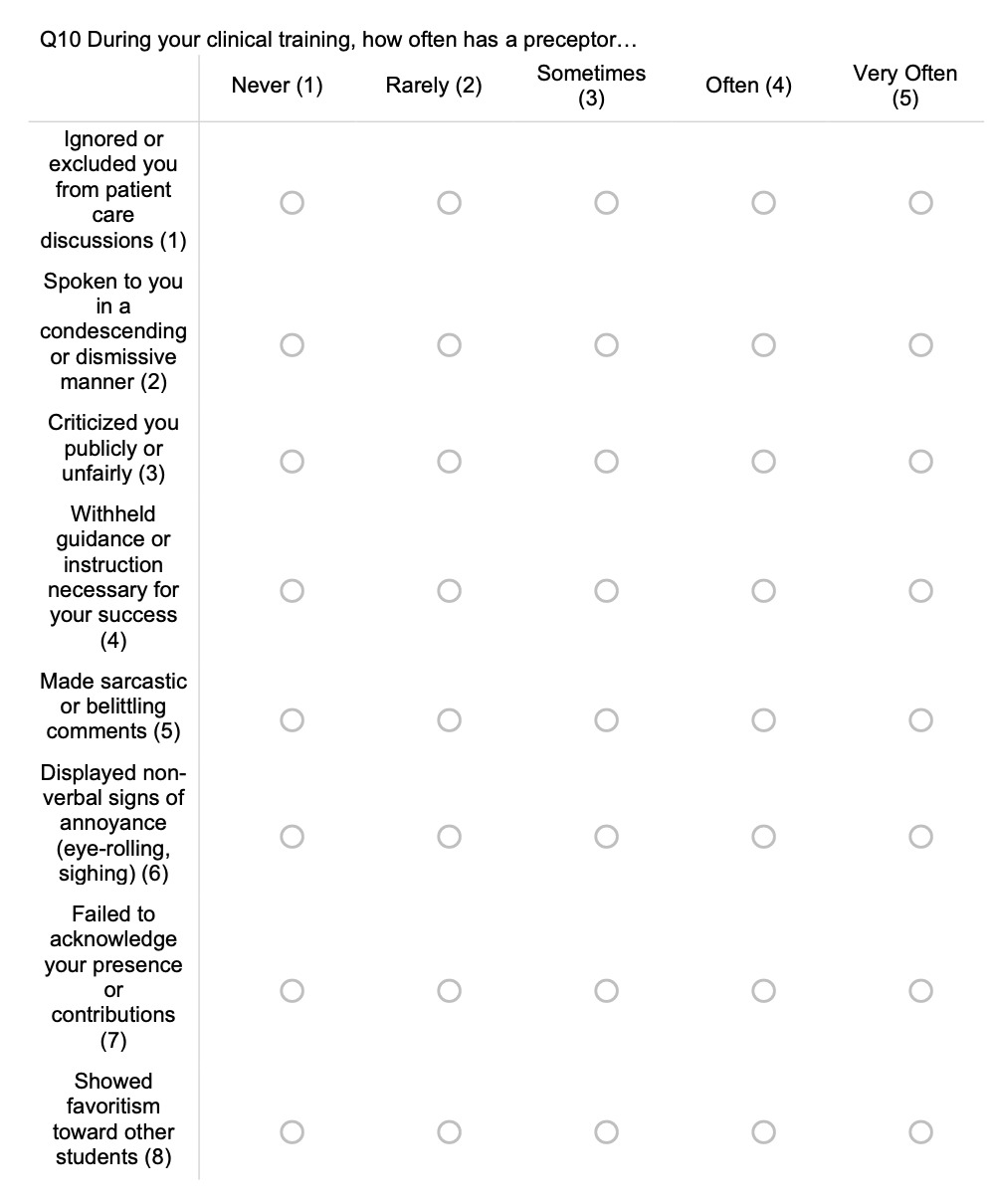

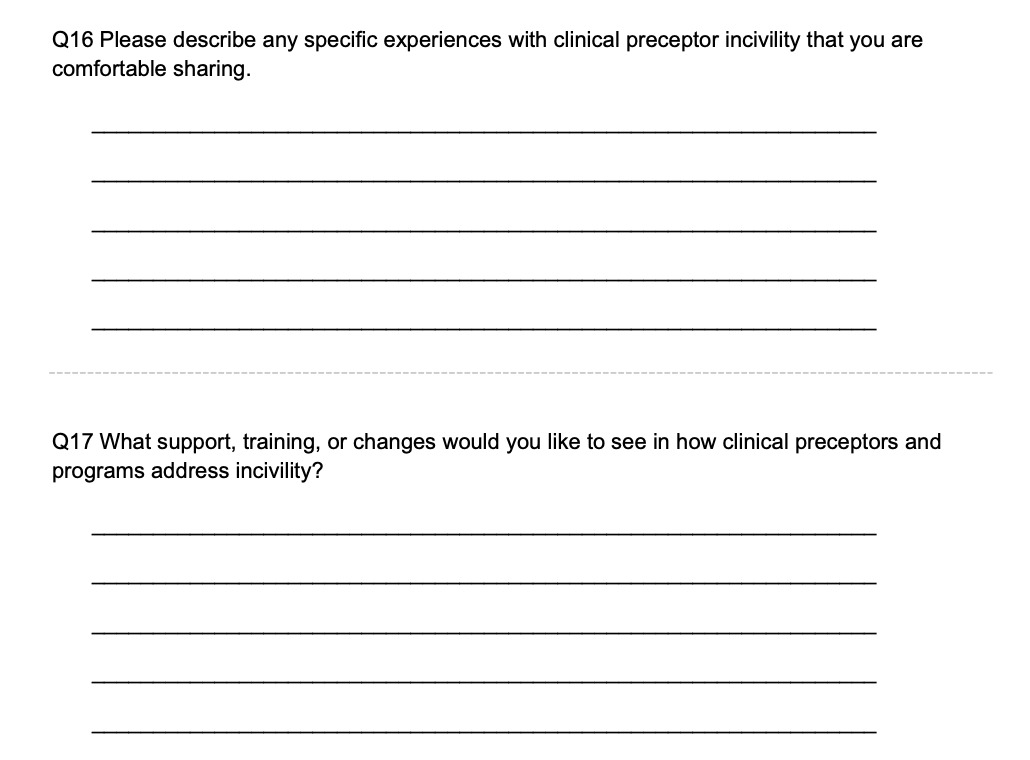

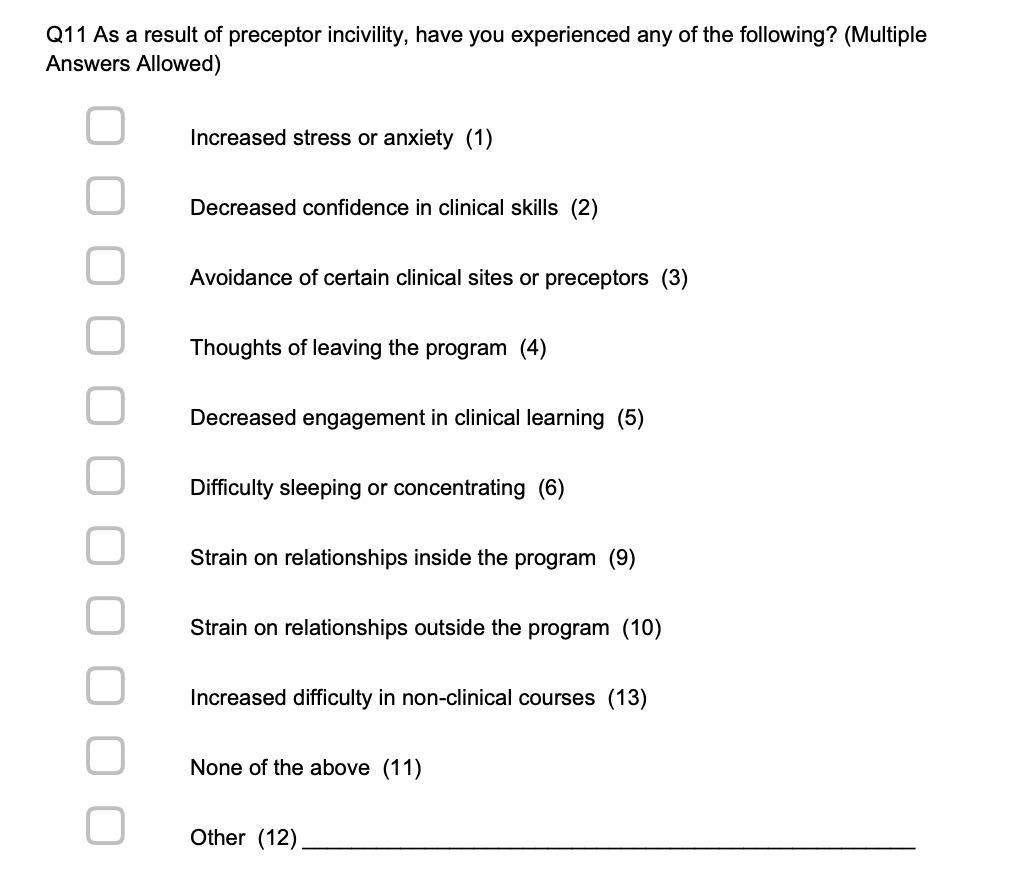

A custom survey tool was developed in Qualtrics to measure the prevalence and nature of clinical preceptor incivility. The survey consisted of both closed-ended Likert-style questions (Figure 1) and open-ended narrative prompts (Figure 2). Items were created to reflect the nurse anesthesiology clinical context, incorporating domains such as: frequency and type of incivility (e.g., verbal dismissiveness, exclusion from learning opportunities, or unfair evaluation); perceived impact on learning, self-confidence, and emotional well-being (Figure 3); reporting behavior and perceived institutional support; and strategies used to cope or respond to incivility.

Content validity was established using expert review. Three nurse anesthesiologists with backgrounds in both clinical preceptorship and nurse anesthesia education independently rated each survey item for relevance using a 4-point scale. Item-level content validity indices (I-CVI) were calculated as the proportion of experts rating items as relevant. The average scale-level content validity index (S-CVI/Ave) was 0.92, indicating strong overall content validity.

Participants

A purposive sample of nurse anesthesiology residents enrolled in accredited Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) and Doctor of Nurse Anesthesia Practice (DNAP) nurse anesthesiology programs across the United States was recruited. Inclusion criteria included being currently enrolled in the clinical phase of training and having experienced or witnessed incivility from a clinical preceptor at any time during clinical training. Participants were recruited via email invitations distributed through program directors, assistant directors, and faculty, and by posting a link to the anonymous survey on nurse anesthesiology social media forums. A total of 313 participants were included in the study. Demographic information such as age, gender, academic year, and type of clinical site (e.g., hospital-based, academic medical center, community hospital) was collected to provide contextual background.

Recruitment and Data Collection

Recruitment occurred from May 2025 through August 2025. Data was collected through a Qualtrics survey sent to program directors, assistant directors, and faculty for dissemination to residents and posted to resident social media forums for voluntary completion. Questions collected demographic data, and several questions were open-ended and designed to elicit participants’ perceptions of incivility, the nature of the behaviors encountered, the emotional and professional impact, and how they responded or coped with the situation. Participation was voluntary, and completion of the survey implied informed consent. No identifying information was collected. Participants could skip any question or exit at any time without penalty. The survey required approximately 10–12 minutes to complete.

Quantitative Data Analysis

Quantitative data were exported from Qualtrics to IBM SPSS Statistics for analysis. Descriptive statistics—including frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations—were utilized to summarize demographic variables and the prevalence of different forms of incivility. Exploratory comparisons (e.g., gender, academic year, or site type) were examined using chi-square tests for categorical variables and independent-sample t-tests for continuous variables where appropriate. Results were considered significant at p < 0.05. Quantitative findings were used to identify patterns of incivility and inform interpretation of qualitative results.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Open-ended responses were analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis. Three researchers independently reviewed all qualitative data and conducted initial open coding to identify salient concepts. Codes were iteratively compared and refined into subthemes and overarching themes using constant comparative techniques. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus, and an audit trail was maintained to document analytic decisions. NVivo 14 software was used to facilitate data organization and coding. Methodological rigor was enhanced through investigator triangulation, peer debriefing, and reflexive memoing to support analytic transparency and trustworthiness.

Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Findings

Integration occurred at the interpretation stage, where qualitative themes were used to contextualize and explain quantitative trends. For example, frequencies of reported incivility behaviors were interpreted alongside residents’ narrative descriptions of the emotional impact and meaning they ascribed to those experiences. This concurrent triangulation strengthened the validity of findings and provided a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon.

Results

Participant Characteristics

A total of 313 nurse anesthesiology residents completed some portion of the survey. Although the survey was distributed nationally to nurse anesthesiology program directors, assistant program directors, or faculty at all accredited programs in the United States, it was not possible to determine how many programs forwarded the survey to their residents. As a result, the exact number of programs represented in the final sample and the proportion of accredited programs contributing respondents could not be calculated. However, the geographic and institutional diversity of respondents suggests broad national participation. The mean participant age was 31.1 years (SD = 4.2), with a range of 25–45 years (Table 1). The majority identified as female (73.81%), followed by male (25.51%), and preferred not to say/other (0.68%) (Table 2).

The number of respondents enrolled in DNP programs was 163 (55.44%), while 129 (43.87%) were enrolled in DNAP programs (Table 3). Distribution across academic years was: Year 1 – 5.48%, Year 2 – 51.03%, and Year 3 – 43.49% (Table 4). Clinical site types were varied: academic medical centers (62.24%), community hospitals (19.39%), urban facilities (9.87%) and private, rural, or specialty practices (8.5%) (Table 5).

Prevalence and Types of Incivility

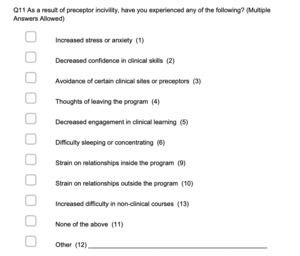

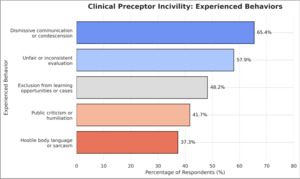

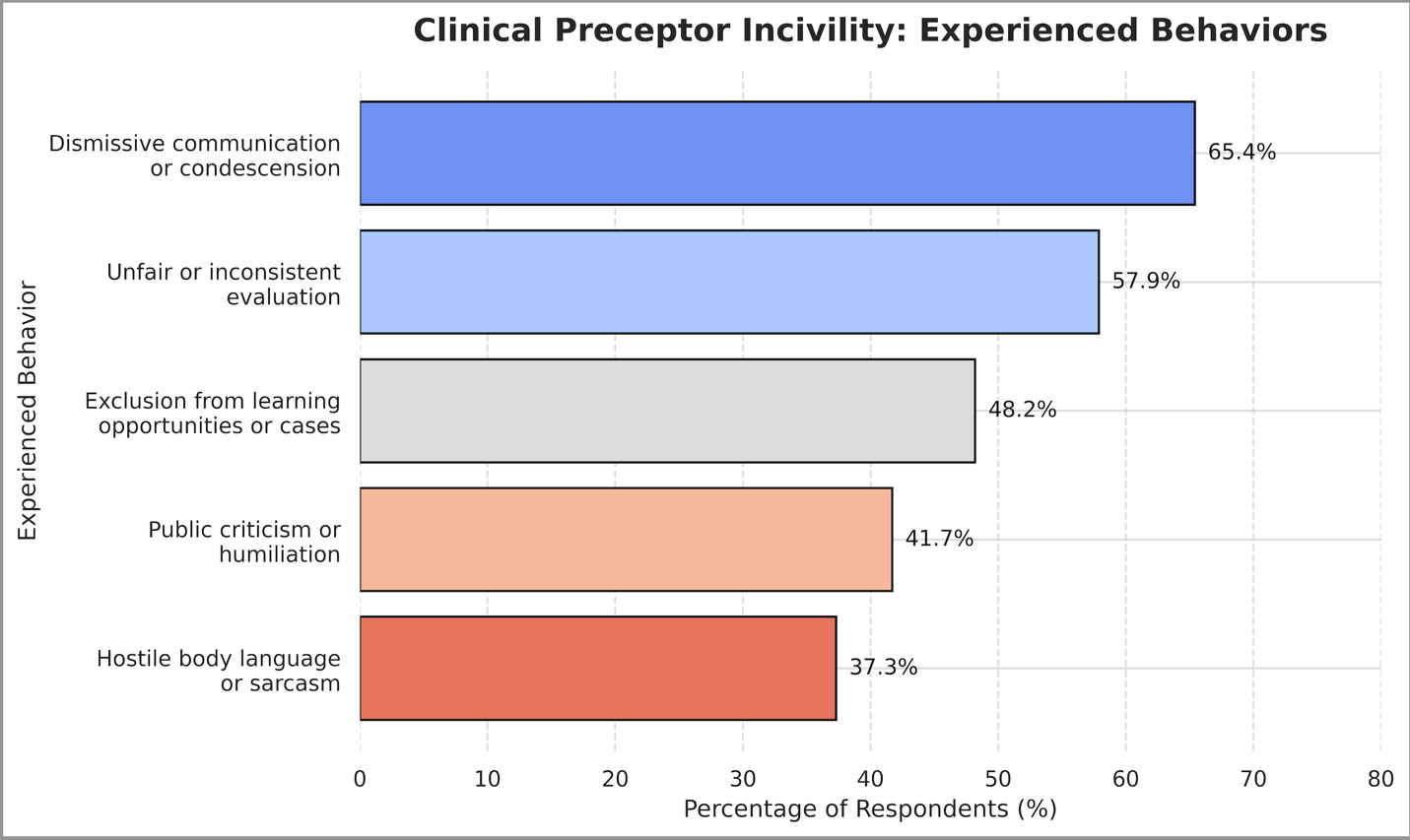

Quantitative findings revealed that approximately 77% of respondents reported experiencing or witnessing at least 1 form of preceptor incivility during their training. Reported behaviors ranged from dismissive condescension to hostile body language and sarcasm (Figure 4). Participants rated the overall frequency of incivility on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Never, 5 = Very Often), and a composite mean score was calculated across items demonstrating strong internal consistency.

The mean overall incivility frequency score was 2.5 (SD = 0.77), with a median of 2.50 (IQR = 2.00–3.00), indicating moderate levels of exposure. When asked to rate the impact of incivility on their learning experience, respondents reported a mean score of 2.57 (SD = 0.89), suggesting a moderate negative effect on perceived educational quality.

A Kruskal–Wallis test revealed no statistically significant differences in incivility frequency scores across clinical site types, H(2) = 1.84, p = 0.161. Although residents in community hospital settings reported slightly higher median incivility scores than those in academic or private/rural/other settings, these differences did not reach statistical significance. Mann–Whitney U testing similarly revealed no statistically significant differences in overall incivility frequency scores between genders. Descriptive trends suggested that incivility exposure increased with progression through the training program.

Reliability and Correlations

Internal consistency reliability of the incivility frequency scale was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and demonstrated excellent reliability (α = 0.91). Spearman’s rank-order correlation demonstrated a moderate positive association between reporting an experience of incivility and overall incivility frequency (ρ = 0.48, p < .001). A strong positive Spearman correlation was also observed between incivility frequency and perceived impact on clinical education (ρ = 0.62, p < .001), indicating that residents who reported higher levels of preceptor incivility perceived greater negative effects on the learning environment.

Qualitative Findings

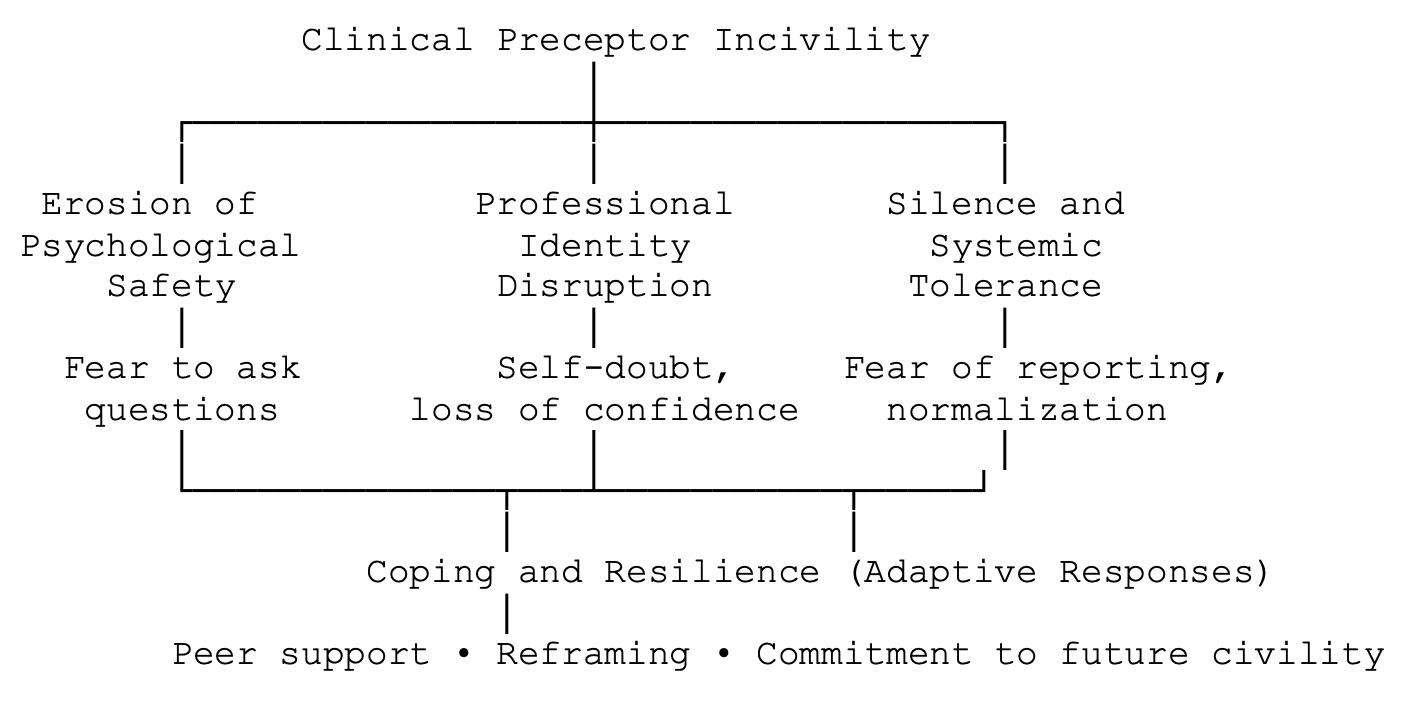

Qualitative data from 272 narrative responses were analyzed thematically. Four major themes emerged which reflect the emotional, professional, and educational implications of clinical preceptor incivility.

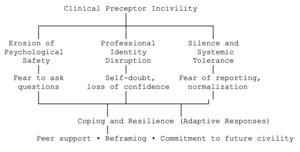

Theme 1: Erosion of Psychological Safety

Residents described feeling intimidated, dismissed, or belittled by preceptors, which inhibited open communication and learning. Many participants reported reluctance to ask questions or clarify clinical decisions due to fear of ridicule.

“Every time I asked a question, my preceptor rolled their eyes or made sarcastic comments. I stopped asking questions altogether because it wasn’t worth the embarrassment.”

Theme 2: Professional Identity Disruption

Several respondents reported internalizing incivility as personal inadequacy, leading to decreased confidence and questioning their competence or career choice.

“When a preceptor tells you you’re not cut out for anesthesia, you start to believe it. I went home questioning if I’d made the right decision to become a CRNA.”

Theme 3: Silence and Systemic Tolerance

Residents described institutional barriers to reporting uncivil behavior, including lack of anonymity, fear of retaliation, and perceived indifference by program leadership.

“We’re told to report issues, but everyone knows it just makes things worse. Nothing changes, and you risk being labeled as difficult.”

Theme 4: Coping and Resilience

Despite negative experiences, many residents developed adaptive coping strategies such as seeking peer support, reframing experiences, or modeling positive preceptor behaviors themselves.

“My classmates became my safe space. We talked about our experiences and tried to learn what not to do when we become preceptors.”

Qualitative findings are illustrated through a code-to-theme development table (Table 6) and a theme map (Figure 5), which visually depict the progression from initial open codes to focused subthemes and 4 overarching themes. Together, these themes represent residents’ experiences of clinical preceptor incivility.

Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Results

The integration of findings revealed strong convergence between quantitative prevalence data and qualitative narratives. Quantitatively, a high proportion of residents reported exposure to dismissiveness, public criticism, and exclusion; qualitatively, these same experiences emerged as central themes influencing psychological safety, confidence, and professional identity formation. Residents who reported higher incivility frequency scores also tended to describe greater emotional distress and reduced learning engagement in their open-ended responses, supporting the correlation between incivility exposure and self-reported anxiety (r = 0.62, p < 0.001). Collectively, these results demonstrate that clinical preceptor incivility is widespread, emotionally distressing, and professionally detrimental, with implications for both individual learning outcomes and the broader culture of nurse anesthesiology education.

Ethical Considerations

An Institutional Review Board (IRB) application was submitted to the Ursuline College Human Subjects Research Committee and was determined to be IRB exempt. Participation was voluntary, and participants’ completion of the study served as informed consent. To protect confidentiality, no identifying information was required in the survey. Participants were reminded that they could withdraw from the study at any time without consequence.

Discussion

Although extensive literature exists on bullying in clinical precepting, residents often remain ill-equipped to manage it. Historically, clinical instructors have been identified as primary sources of bullying in clinical settings, leaving residents without adequate support or preparation to respond effectively. Given the high prevalence of incivility in clinical environments, educators hold a crucial responsibility in addressing these behaviors and equipping residents with the skills to do the same.9

This study explored the lived experiences of nurse anesthesiology residents who encountered incivility from clinical preceptors. The findings confirm that incivility is present in the clinical learning environment of nurse anesthesiology education, often manifesting through behaviors such as dismissiveness, demeaning language, exclusion from learning opportunities, and inconsistent feedback. These findings align with previous literature in broader nursing education, which identifies clinical incivility as a significant barrier to student engagement, confidence, and professional development.

A key theme that emerged was the power imbalance between residents and preceptors. Residents reported difficulty addressing uncivil behaviors due to fear of retaliation, negative evaluations, or damaged professional relationships. This dynamic echoes existing findings in undergraduate nursing education and is exacerbated in nurse anesthesiology by the hierarchical and high-pressure nature of the perioperative environment. Neiterman et al10 examined strategies that could be used to improve the preceptor-student relationship to facilitate student retention and how these relationships impact student views. The authors found that reducing the power imbalance inherent in preceptor–student relationships enhances student confidence and fosters more positive, constructive learning experiences. Providing additional training for preceptors, implementing educator oversight of mentorship practices, and establishing ombudsperson roles are potential strategies to help lessen these power differentials.10

Participants also described the emotional toll of incivility, including anxiety, self-doubt, and a sense of isolation. For many, incivility was internalized as a reflection of their inadequacy, even when the behavior was clearly unprofessional. Some residents questioned their competence or future in the profession, suggesting that incivility can contribute to burnout and attrition, which are critical concerns in an already demanding specialty. Notably, some residents developed personal coping strategies, such as seeking mentorship, reframing the experience, or using peer support to process emotions. However, coping mechanisms were not always effective or sustainable, particularly in the absence of institutional support or a clear reporting pathway.

The findings underscore the need to shift away from normalization of “tough love” or “old-school” teaching tactics that may perpetuate incivility under the guise of professional rigor. While high expectations are necessary in anesthesia training, respect, clarity, and psychological safety are essential for learning. These types of behaviors can have impacts beyond those who are targeted. Patients who witness incivility may lose trust in both the institution and their healthcare team. A culture that tolerates preceptor incivility not only jeopardizes resident well-being but also risks creating future CRNAs who repeat the same behaviors.11

The authors acknowledge that several limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings. Data were collected via self-reporting, which introduces the potential for reporting and recall bias. The cross-sectional design precludes assessment of causality or changes in experiences over time. Recruitment relied on dissemination through program leadership and professional social media platforms, which may have contributed to self-selection bias and potential overrepresentation of individuals with particularly strong or salient experiences related to clinical preceptor incivility. As such, findings reflect residents’ perceptions at a single point in time and may not fully represent the experiences of all nurse anesthesiology residents.

It is important to note that not all clinical preceptors engage in uncivil behavior, and some may be unaware of the impact of their communication style. System-level constraints, including staffing shortages, productivity pressures, and high-acuity clinical demands, may unintentionally contribute to strained interactions. In 1 study, 72% of CRNAs practicing in an academic medical center reported symptoms of burnout. This finding underscores that burnout extends beyond individual distress and represents a systemic concern with potential implications for patient safety, quality of care, and clinical decision-making.1 As a perception-based survey, findings reflect residents’ experiences and may differ from preceptor perspectives.

Clinical preceptors operate under significant professional and systemic pressures that may influence their behaviors and communication styles. Recent literature suggests that preceptors frequently experience role strain related to competing clinical demands, productivity expectations, time constraints, and limited formal preparation for educational roles, all of which may contribute to interactions that are perceived by learners as uncivil but not necessarily intended as such. Studies of nurse and advanced practice preceptors have shown that many preceptors report high levels of workload stress, emotional exhaustion, and insufficient institutional support for teaching responsibilities, which can affect their capacity for reflective communication and feedback delivery.12 Cultural norms and institutional values influence how behaviors are interpreted, indicating that perceptions of preceptor incivility may vary across educational and organizational cultures. Recognizing preceptor perspectives and contextual factors is therefore essential for interpreting resident experiences and for developing balanced, system-level interventions that address both learner well-being and preceptor support needs.13

Implications for Practice

Although nursing has long been recognized as a caring profession, it has also been associated with poor collegial relationships. Mammen et al14 references a New York Times article published in 1909 that described “abominable outrages” among nurses, citing instances in which head nurses misused their authority. This historical account suggests that workplace incivility has been present in nursing for more than a century. Negative behaviors may range from mild rudeness to severe workplace bullying. Although such actions may not always be intended to cause harm, there is no assurance that harm can be avoided.14

This reality is reflected in the findings of the survey of nurse anesthesiology residents, in which 77% of respondents reported experiencing at least 1instance of incivility from a clinical preceptor. Despite this prevalence, only 22% of those who experienced incivility chose to report it. Among those who did not report, 32% indicated that the incident was not serious enough, 24% feared retaliation, and 25% believed that reporting would not be beneficial. Another 21% cited other reasons. Notably, while 10% of respondents stated that incivility had no negative impact on their clinical education, the majority perceived these interactions as detrimental, underscoring that even unintentional acts of incivility can have lasting consequences for learners. Consequently, in 2019, the World Health Organization identified chronic workplace stress as a key driver of burnout—characterized by enduring psychological, emotional, and physical strain within the work environment. As the burnout crisis has drawn growing concern both within and outside healthcare, increasing attention has turned to the concept of civility as a meaningful and proactive approach to mitigating its effects.15

Preceptor development should include civility training. Addressing barriers identified by both advanced practice providers and students is essential for strengthening the clinical preceptorship model. Common obstacles to effective preceptorship include inadequate preparation, limited experience, and the absence of evidence-based mentorship guidelines, all of which can contribute to strained preceptor–student relationships and mutual frustration. The literature also highlights factors such as excessive workloads, ambiguous expectations, and insufficient time for teaching as persistent challenges faced by preceptors. Implementing structured preceptor training programs and workshops has been shown to mitigate several of these barriers and enhance the overall quality of clinical learning.16 Nurse anesthesiology programs should formally educate clinical preceptors on civility, feedback strategies, communication skills, and professional boundaries. Content should focus on the impact of incivility on learning and patient safety, as well as tools for promoting psychologically safe environments. This may be integrated into annual clinical faculty training or onboarding modules.

Nurse anesthesiology residents should have a clear reporting structure within programs and clinical facilities. Programs must establish confidential, non-punitive pathways for residents to report incivility without fear of reprisal. This should include clear definitions of incivility, examples of unacceptable behavior, and procedures for addressing concerns. Empowering residents to report uncivil behaviors from preceptors is essential for program accountability and culture change.

Fostering reflective dialogue between faculty, preceptors, and nurse anesthesiology residents is essential to resident success. Encouraging structured debriefs, midpoint check-ins, and anonymous feedback systems can promote bidirectional communication. Preceptors who receive timely, constructive feedback are more likely to adjust behaviors, while residents benefit from knowing their voices are heard.

Several key implications for educators emerge from this study. First, clinical incivility, whether intentional or unintentional, has meaningful consequences for resident confidence, learning engagement, and professional identity formation. Second, power differentials and institutional silence continue to limit residents’ willingness to report concerns, underscoring the need for transparent and psychologically safe reporting systems. Third, preceptor development programs must address not only clinical teaching skills but also emotional intelligence, feedback delivery, and awareness of implicit communication patterns. Finally, sustainable culture change requires shared accountability among academic programs, clinical affiliates, and professional organizations to prioritize civility as a core component of clinical excellence and patient safety.

Programs should actively promote open dialogue about well-being, burnout, and resilience to demonstrate that psychological safety is a core value in clinical education. Cultivating a culture of psychological safety in nurse anesthesiology training demands deliberate actions. Faculty must model professionalism, and program leaders must respond to uncivil behavior promptly and transparently. Further multi-institutional research is needed to examine the prevalence, underlying causes, and effective strategies for addressing incivility in nurse anesthesiology education. Program-level data can then guide focused interventions and measure progress toward creating safer, more supportive clinical learning environments, ultimately leading to improved patient outcomes.

This study demonstrates that clinical preceptor incivility is a prevalent and consequential issue in nurse anesthesiology education, with meaningful implications for psychological safety, professional identity formation, and resident well-being. The findings suggest that incivility during clinical training is not an isolated interpersonal problem but a systems-level challenge that may contribute to burnout, disengagement, and attrition within an already strained workforce. Addressing clinical preceptor incivility therefore requires intentional, coordinated efforts by nurse anesthesiology programs and clinical partners, including structured preceptor development, transparent and non-punitive reporting mechanisms, and a shared commitment to professional accountability. Such efforts are essential to fostering respectful learning environments, supporting resident success, safeguarding patient care, and sustaining the future of the nurse anesthesiology profession.